Key Takeaways

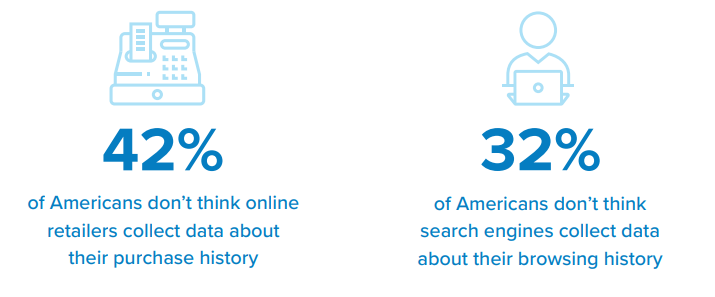

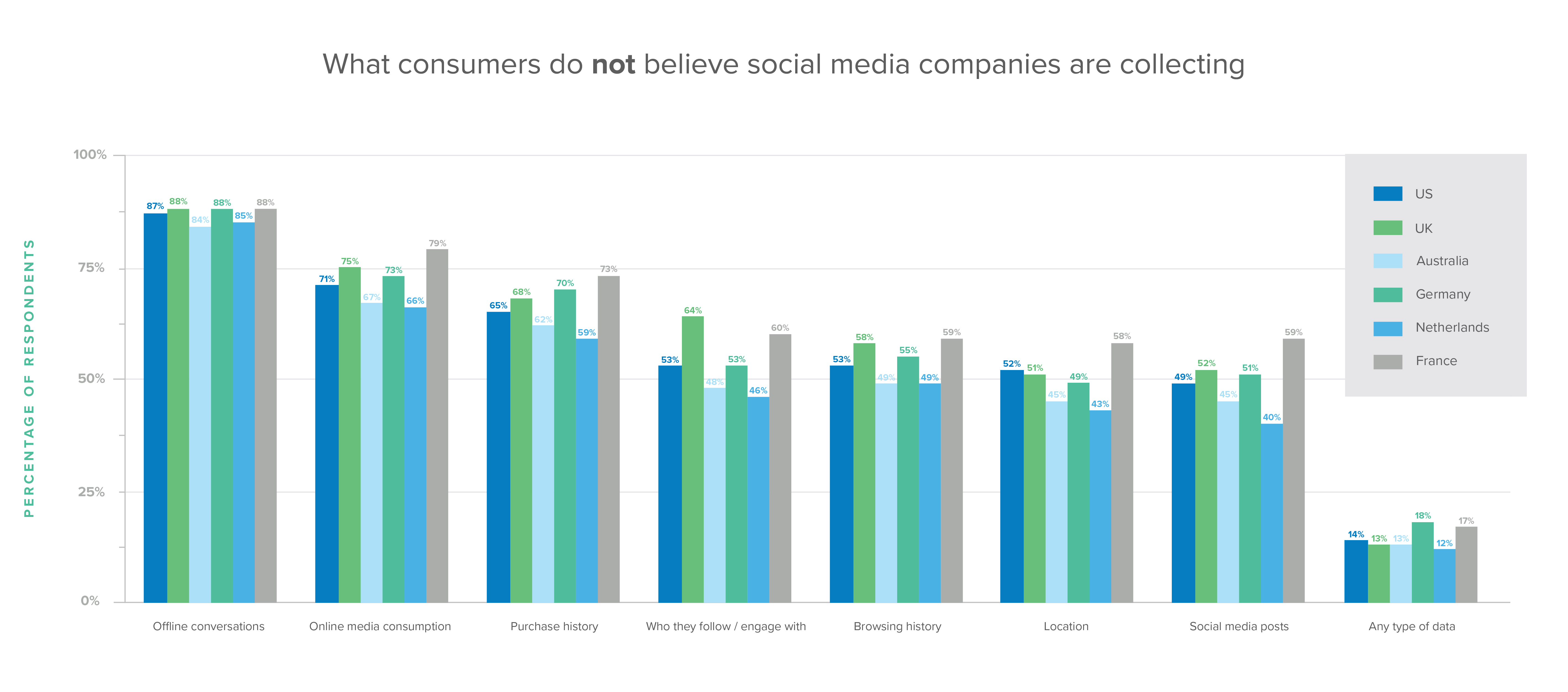

1 Consumers underestimate the extent to which their data is being tracked

A significant number of respondents believe companies are not collecting data about their online and offline activities. 42% of Americans do not think online retailers collect data about their purchase history, and 49% do not think their social media posts are being tracked by social media companies. But COVID-19 may be closing the education gap: 65% of Americans are aware of efforts to track the spread of COVID-19 through smartphone data collection, and 1 in 4 say the pandemic has made them more aware of data tracking efforts.

2 Consumers say privacy outweighs all, including tracking the spread of COVID-19

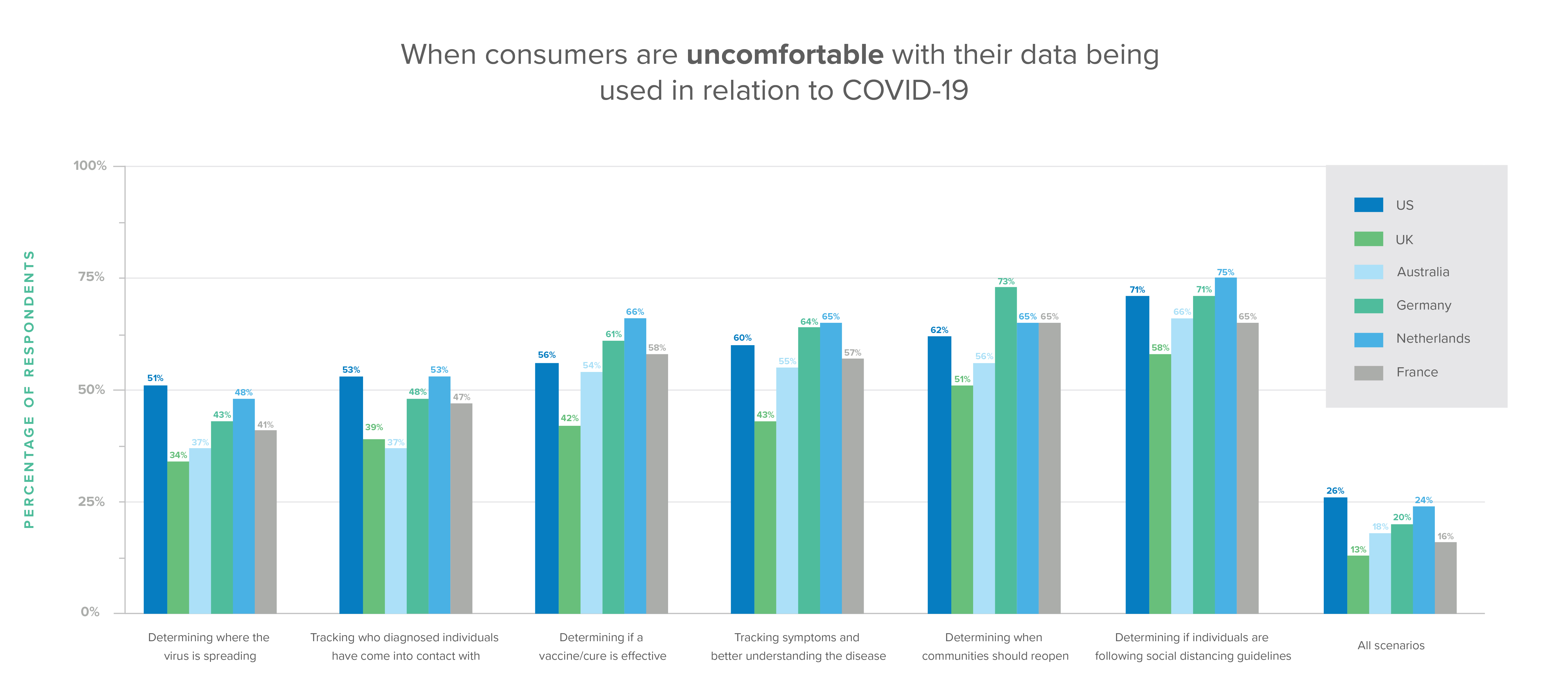

While technology companies have launched promising initiatives to track the spread of COVID-19, many consumers aren’t buying it. 84% of Americans are worried that data collection for COVID-19 containment will sacrifice too much of their privacy, and 74% of Australians say the same. While just over half of Americans (53%) are uncomfortable with data collection for contact tracing, discomfort levels increase when it comes to using data to track social distancing compliance (71%) and to determine when communities should reopen (62%).

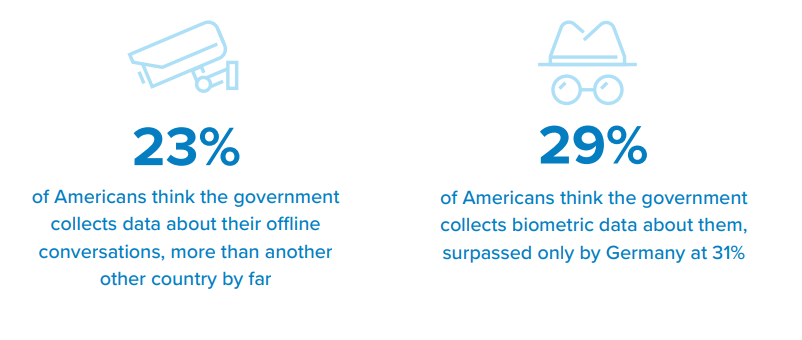

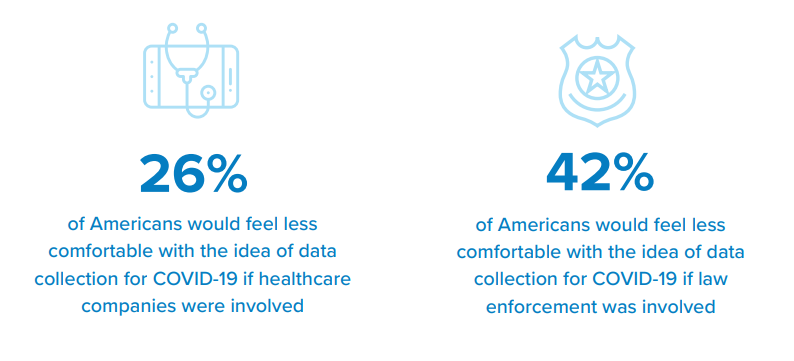

3 Distrust in government is high

While social media companies are the least trusted overall, global respondents make it clear that governments are still in hot water. 70% of Americans are uncomfortable with the government tracking their data, and less than a quarter (24%) of US respondents are willing to share their data to help law enforcement. When it comes to the global pandemic, 45% of Americans say government involvement makes them less comfortable with the idea of data tracking for COVID-19 containment, while only 27% of UK respondents say the same.

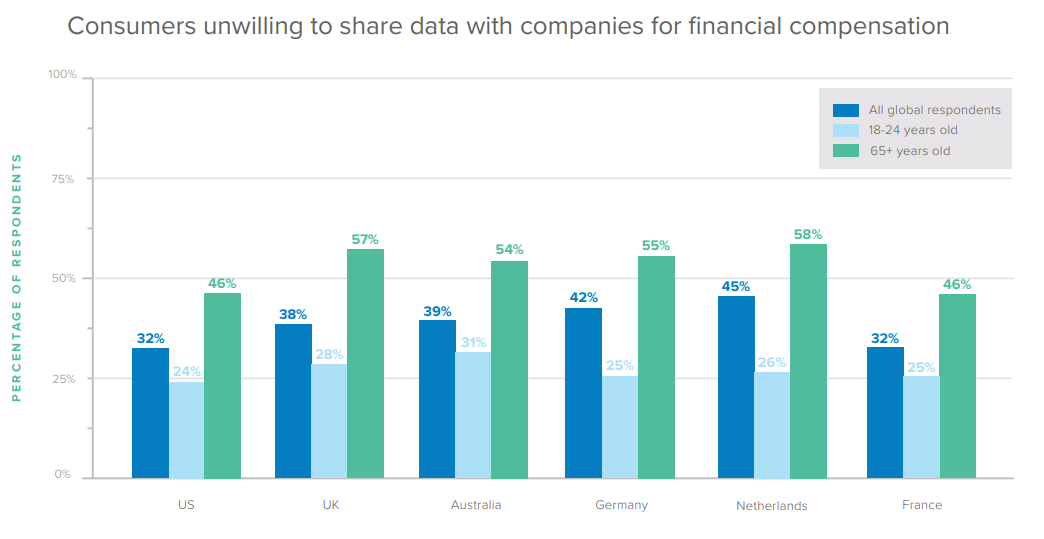

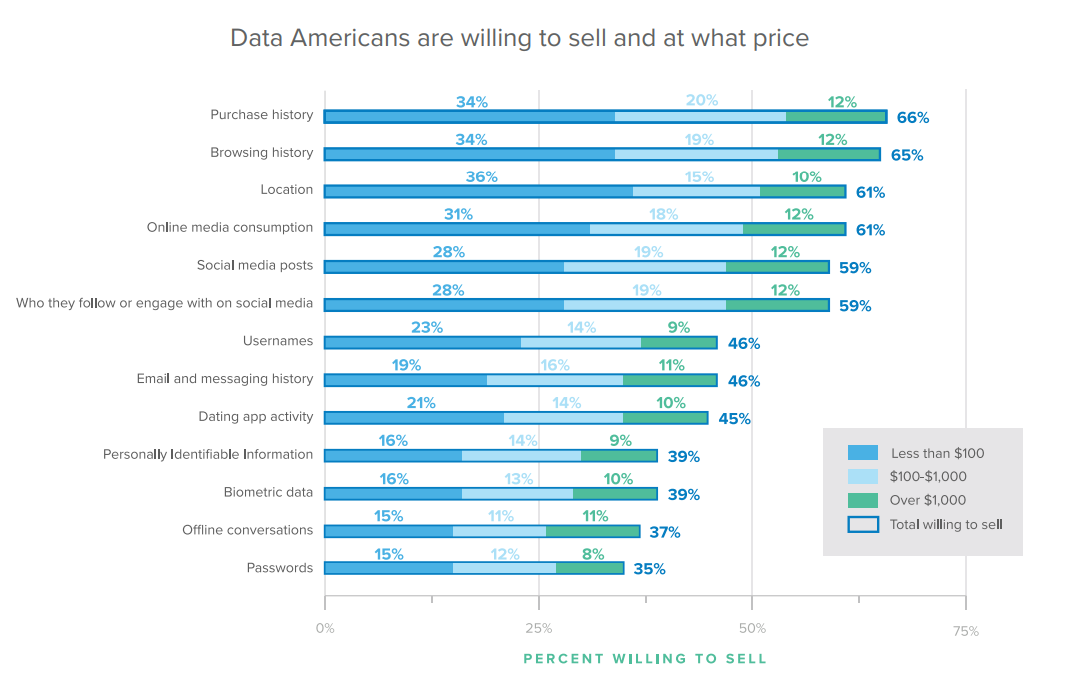

4 Consumers are sitting on gold mines of data,but many won’t cash in

We asked global consumers if they’d be more willing to share data with companies if they were financially compensated, and 37% say no. Another 27% are unsure if payment is worth it to sacrifice their data. When it comes to specific types of data, 76% of all respondents are unwilling to sell some portion of their data. Ultimately, consumers value data privacy more than some extra cash.

5 Identity verification is taking a toll on democracy, but mail-in ballots could help

14% of Americans who are not registered to vote report avoiding registering because of complications with the registration process — a number that adds up to millions of votes that could affect election outcomes. We also asked about the impact of COVID-19 on the 2020 US election, and 67% support the use of a mail-in ballot system to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus.

Introduction

Companies are collecting all kinds of data about our online activities, whether we are browsing the Internet, watching online content, or posting on social media. Together, this record of our data makes up our digital identity. However, there is no official list of what data is collected, leaving consumers confused about where they are being tracked and what data is associated with them. Across the board, people are distrustful and uncomfortable about how their data is being used by companies and governments, even when it comes to noble causes like tracking the spread of COVID-19. Two things are certain: people don’t want to be tracked, and they place a high value on privacy.

The unintended ramification is a cost for getting the digital privacy people so badly desire. Data tracking benefits companies in many ways, especially those that directly profit from selling consumer data. As a result, consumers often have to sacrifice their privacy to access services they want or need, leading to decreasing levels of trust. There is also an unintended tax on citizens’ time as they struggle to prove their identity repeatedly each year. Perhaps most concerning, there is a real impact on voter turnout, at levels which undoubtedly affect elections. These “4 Ts” (tracking, trust, time, and turnout) reveal the tradeoffs that consumers face as they use online services and seek some level of digital privacy.

To better understand how people perceive both their digital identity and how it is managed, Okta commissioned Juniper Research to conduct an online survey of over 12,000 people between the ages of 18 and 75 in six countries: Australia, France, Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States. When COVID-19 changed our world, Juniper went back and asked nearly 6,000 of those original respondents how the pandemic has affected the way they think about privacy. The respondents were selected on a nationally representative basis of age, gender, and location. This report will summarize the findings of that survey.

A Digital Identity Crisis: Consumers Have a Fuzzy Vision of Their Online Presence

Privacy has become a hot-button issue over the last few years as consumers worry about who collects, stores, and uses their personal information. But exactly what personal data is being collected? Most consumers vastly underestimate the breadth of data used by companies to identify individuals online.

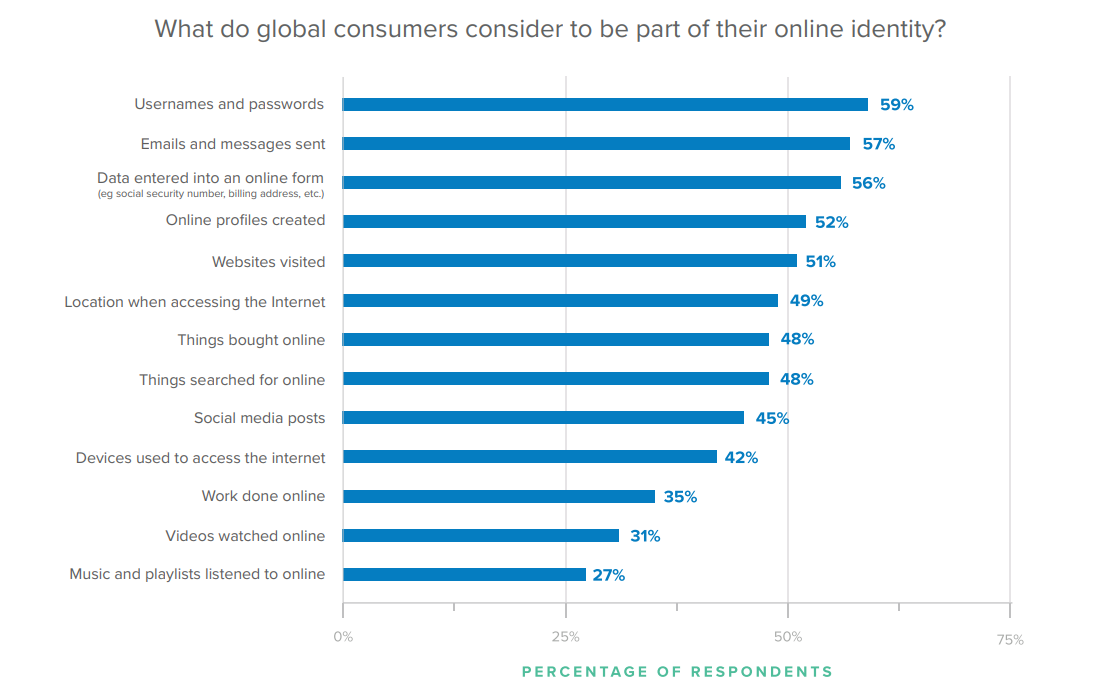

Consumers have significant blindspots when looking at their digital identities

When looking at a list of 13 different types of commonly tracked online data — such as usernames, browsing history, and social media posts — the average survey respondent believes only 6 of these types of data constitute their online identity. This is fairly consistent across all countries surveyed, besides France. There, respondents believe an average of 5 types of data make up their digital identities, demonstrating the lowest understanding.

On average, American consumers believe 6 types of data make up their online identity.

News flash: women and boomers are more identity-conscious

Women are consistently more aware of the types of data that are contributing to their online identities than men.

For example, American women are 15 percentage points more likely to think their social media posts are a part of their online identity. 59% of them believe data entered into a form, such as a Social Security number, birthdate, or billing address, is associated with their identity, compared to 46% of men. And when it comes to location data when accessing the Internet, 53% of American women think it counts toward their digital identity compared to only 43% of men.

The same can be said of older generations. American respondents between the ages of 18-24 say an average of 5 types of data contribute to their online identities, in contrast to those ages 65 and up who average 7 types of data. Other countries surveyed showed similar trends.

Is Ignorance Bliss? Consumers Underestimate the Extent to Which Their Data is Being Tracked

There is a common expression that says, “if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product.“1 The Internet provides a wealth of information and services that consumers now think of as “free,” but they often forget that their “free” email address, Internet search, and social media account are being funded by advertising dollars, and those advertisers are buying access to them, the end user.

From Cambridge Analytica to Google’s collection of millions of Americans’ medical data, a never-ending list of controversies have shed a light on consumers’ shrinking levels of privacy. Yet, our data shows that many consumers are not aware of the routine tracking and data harvesting that takes place daily.

Dance like no one is watching... or listening

A significant number of respondents believe their online and offline activities are not being tracked. Nearly 4 out of 5 American respondents (78%) don’t think a consumer hardware provider such as Apple, Fitbit, or Amazon is tracking their biometric data, and 56% say the same about their location data. 75% of Americans don’t believe streaming services are collecting information about their online media consumption, and 80% don’t think their broadband provider does either.

Online communications are also presumed to be private by a surprising number of respondents. 52% of Americans don’t think email providers are tracking their email and messaging history, and 74% say the same of their employer.

Despite the bad press, many consumers aren’t aware of social media tracking

As consumers scroll through their feeds, they have a general awareness that social media companies are tracking something: over 80% of respondents in all markets believe that social media companies are tracking at least one element of their data.

Respondents from the Netherlands are the most likely to expect a social media company to actively collect data on their social media posts: only 40% do not think this data collection is occurring. In contrast, 59% of French respondents do not think their posts are being tracked by social media companies, and 49% of Americans agree.

Tracking a pandemic

People are inundated with COVID-19 news, consuming constant updates about case counts, reopening plans, and potential strategies for fighting the pandemic. Yet, 35% of Americans are unaware of efforts to track the spread of COVID-19 through smartphone data collection. While this level of awareness is higher than most other types of data we asked about, respondents in other countries are far more informed. Only 4% of Australians, 14% of Dutch respondents, and 17% of Germans are unaware of data tracking efforts to contain the novel coronavirus.

23% of Americans are more opposed to data tracking in the wake of COVID-19.

Still, COVID-19 may be closing the data tracking education gap: 1 in 4 Americans say the pandemic has made them more aware of data tracking efforts (26%) as well as the possible benefits of data tracking (25%). In the UK, 32% and 31% of respondents say the same, respectively.

Distrust and Discomfort in the Age of COVID-19

Whether or not consumers understand what is being tracked, they are generally unhappy that companies are tracking their data, regardless of why it’s being collected. Across all countries surveyed, 91% of consumers are uncomfortable with at least one kind of organization tracking their data.

Though if there’s ever been a time to justify the sacrifice of digital privacy, COVID-19 is it. While companies like Apple and Google are making a concerted effort to safeguard consumer privacy while tracking the spread of the virus, respondents still feel uncertain about the potential privacy and security ramifications.

Freedom over everything: Americans won’t give up their data to slow the spread of COVID-19

Americans show widespread discomfort with the idea of their data being collected to aid the containment of COVID-19. A majority of Americans say they are uncomfortable with personally identifiable information (67%), bluetooth data (57%), medical data (53%), and location data (52%) being collected. Consistently, older respondents (ages 65-75) are more comfortable with the idea of data collection to track the virus than younger respondents.

In the UK, respondents are far more willing to sacrifice their data to stop the pandemic. Only 51% are uncomfortable with their personally identifiable information, 43% with their bluetooth data, 39% with their medical data, and 40% with their location data being collected.

Across all countries, discomfort levels rise when asked about data being used in scenarios that regulate individual behavior, such as enforcing social distancing or determining when communities should reopen.

Privacy and security concerns swell during COVID-19

While the public health benefits of collecting data to track the spread of COVID-19 are clear, consumers in every country surveyed are worried about privacy. A whopping 84% of Americans worry they will be giving up too much of their privacy, and 81% of Germans and 74% of Australians agree. Security is another looming concern, with 87% of Americans worrying that data collection for COVID-19 will make their data insecure. This is an even bigger concern in the Netherlands, where 90% express concern.

Trust, or lack thereof, is a big part of the problem. 86% of Americans worry their data will be used for purposes other than COVID-19. This was the number one concern in Australia (79%), Germany (87%), and the UK (84%).

We asked what could be done to make consumers feel more comfortable with their data being tracked for COVID-19 containment, but a consensus couldn’t be reached. 30% of Americans say nothing can be done to make them feel more comfortable, the highest of any country. 47% say a limit on who can access the data would do the trick. Other solutions include: needing to give explicit consent (39%), putting a limit on how long the data can be tracked (37%), making sure data isn’t shared with organizations outside of the US (35%).

While it is clear that privacy is a concern, the root of the problem may be uncertainty around whether smartphone-based data collection is an effective way to slow the pandemic. 54% of Americans said they believe it is not effective, and only 10% believe it is very effective. Australians are the most optimistic, with 62% believing in the efficacy of smartphone tracking.

Never say never: some consumers see benefits of data collection

28% of global respondents say COVID-19 has made them more open to the possible benefits of data tracking. But even before the pandemic hit, over half of all respondents were amenable to some form of data collection in exchange for personal and community benefits.

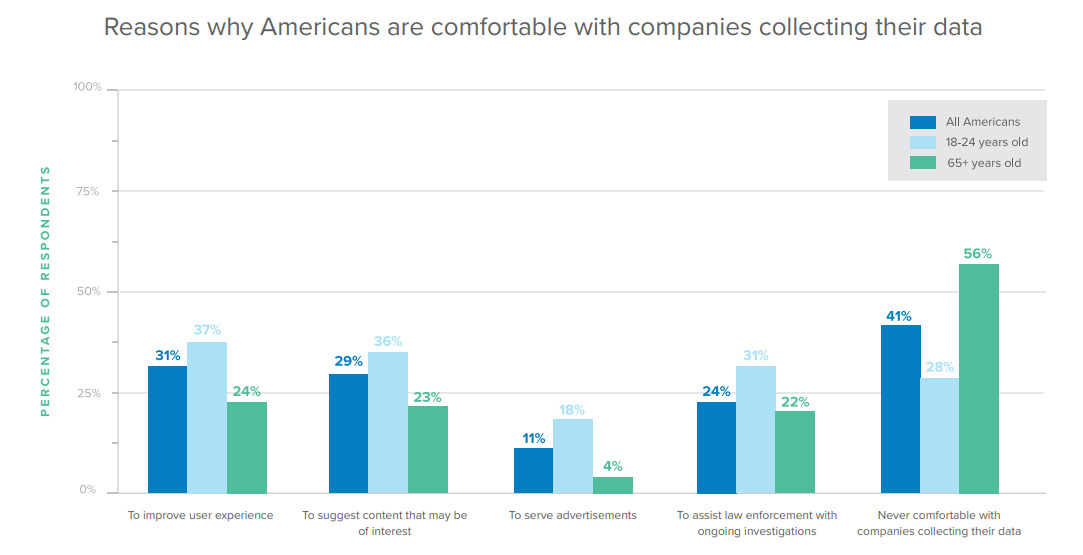

Across the board, Americans in the 18-24 age group are the most likely to be comfortable with data collection in order to receive some type of benefit in return, whether that be an improved user experience (37%) or relevant content (36%).

Consumers draw the line when it comes to helping law enforcement. The vast majority of respondents don’t think the benefit is worth the cost, despite conversations about how facial recognition technology and genetic data can aid police investigations. Consumers in the Netherlands are the most willing to share their data to help law enforcement, at 31%. Less than a quarter (24%) of Americans are willing, and only 22% of Germans say the same.

Not All Data Is Created Equal

Respondents across every country make it clear that protecting their privacy is a priority, but of course, they consider some types of data more valuable than others.

In the US, respondents are the least concerned about organizations tracking their purchase history and online media consumption, with 59% expressing concern. Biometric data, dating app activity, and email and message history are all top concerns.

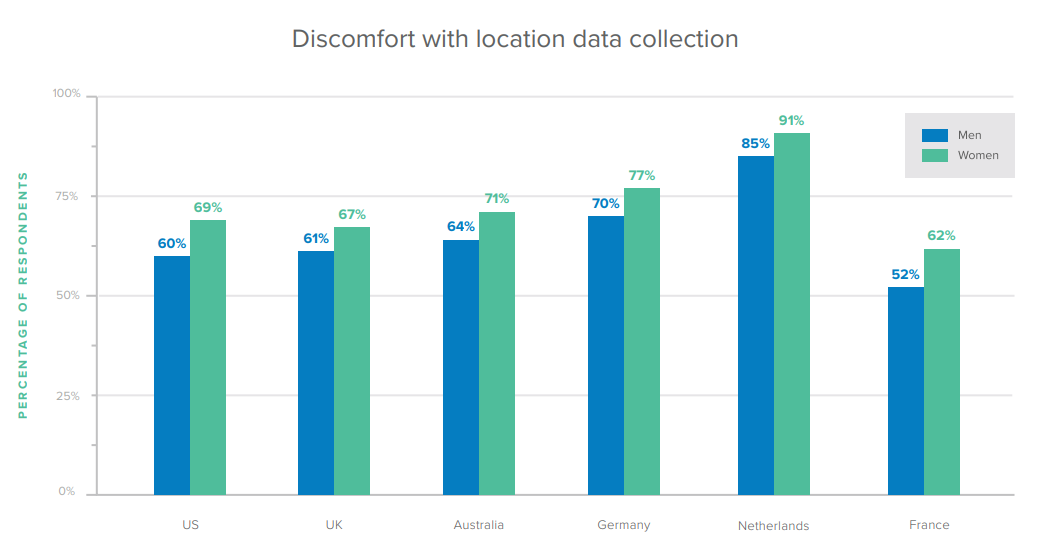

Location, location, location: consumers dislike location tracking

Location data is the most common type of data that global consumers think companies are tracking, yet at least 57% are uncomfortable with their location being tracked. Consumers see buzzy articles about how to correctly set the privacy settings on smartphones, but those can give a false sense of security: Google was exposed for storing location data on smartphones even if the consumer had used a privacy setting that said it will prevent Google from doing so. 2

In the US, 65% of Americans are uncomfortable with their location data being collected. Across all countries surveyed, an interesting trend emerges: women are between 6-10 percentage points more uncomfortable with the issue than their male counterparts.

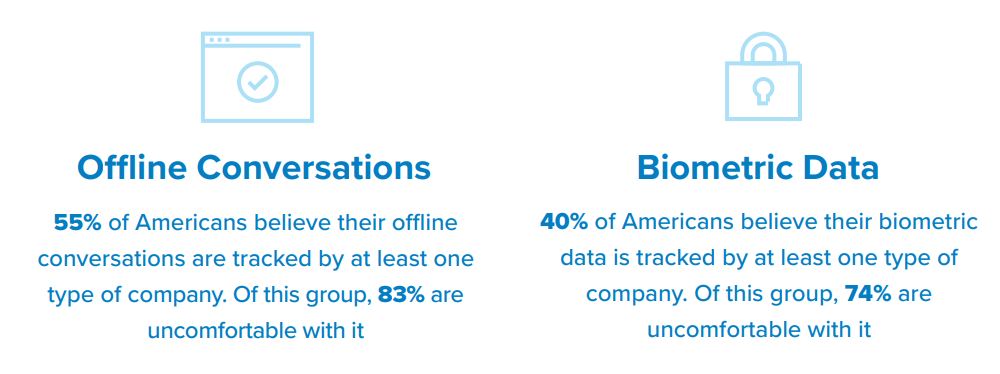

Protecting “real life” data

Almost half of all respondents believe their offline conversations and biometric data are being tracked by at least one kind of company online, although there is little consensus as to which kinds of companies are engaging in the data collection. Respondents in the Netherlands show the highest rate of discomfort, with 90% saying they are uncomfortable with offline conversation tracking, and 88% are uncomfortable with biometric data collection.

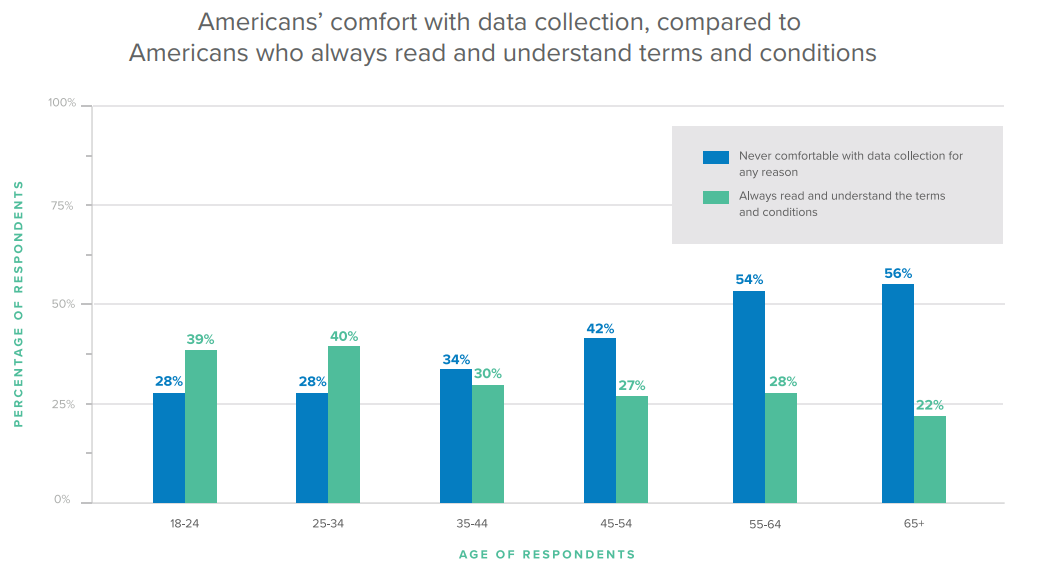

Older and wiser, or just not interested in the fine print?

Data collection sentiments are directly linked to the age of the respondents. 41% of Americans are never comfortable with any form of data collection for any reason, but when broken out by age, the difference is striking. Of respondents ages 18-24, 28% are never comfortable with data collection, compared to 56% of respondents ages 65 and up. This disparity between generations is consistent across all countries surveyed.

One explanation is that younger respondents are more likely to take the time to educate themselves about the uses of their data. In the US, only 31% of respondents always read and understand the terms and conditions of a digital services website. However, when broken down by age, we find that younger respondents are much more likely to read terms and conditions than older respondents.

Crossing the line: consumers do not want companies profiting off their data

Compared to data collection, an even bigger concern for a majority of consumers is that companies are profiting from their data. 93% of all respondents are uncomfortable with companies selling some portion of their data, and 67% are uncomfortable with any form of their data being sold.

Nine out of 10 Americans (90%) are uncomfortable with companies profiting from at least one type of their data. The sale of biometric data, passwords, and offline conversations cause the most concern at around 80% each. Browsing data and purchase history are of the lowest concern, but 73% and 74% of Americans respectively still report being uncomfortable with companies selling this data.

A Trust Problem: Does it Matter Who is Tracking?

The answer is yes: it matters who is tracking your data. Although 46% of all respondents are uncomfortable with data tracking in any form, consumers in all countries surveyed have varying comfort levels depending on what type of organization is collecting the data.

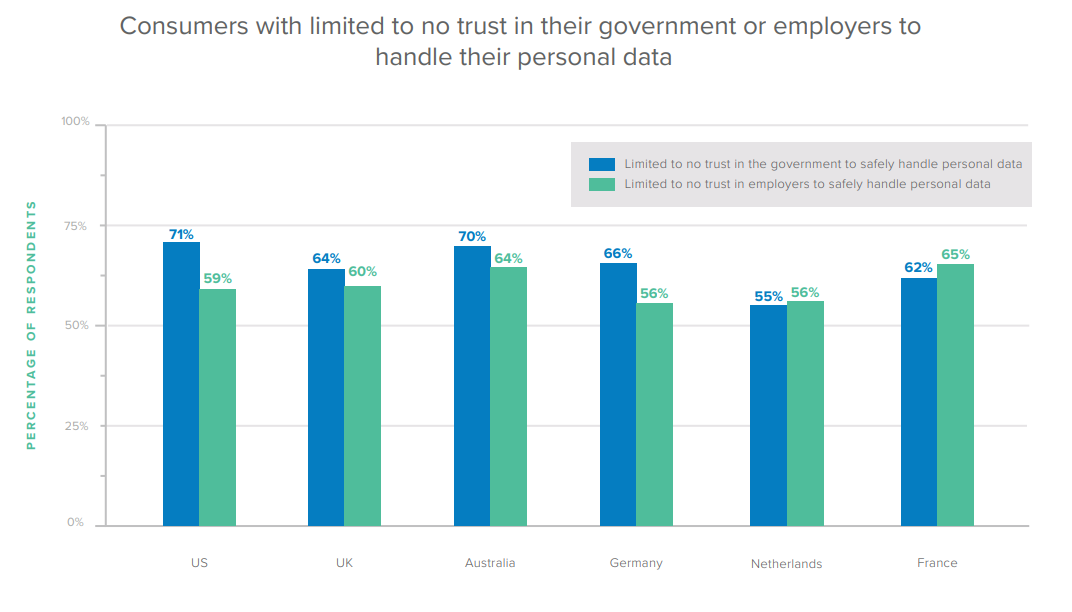

Distrust in government: big brother is watching

The idea that the government tracks consumer data is a big concern for all respondents, especially in the US (70%), Netherlands (73%), and Germany (74%).

In the US, trust in the government’s ability to safely handle personal data is particularly low, with 71% saying they have limited to no trust in the government’s ability to do so. When you break down the respondents by age, a clear divide emerges. 56% of Americans ages 18-24 very much trust the government’s ability to safely handle their personal data, while only 25% of Americans ages 55-64 feel the same way.

In the US, UK, Australia, and Germany respondents report significantly higher trust in their workplace to handle their personal data than the government.

Survey respondents also believe the government is the most likely group to collect their biometric data and offline conversations. Social media companies and search engines take a fairly distant second and third, respectively.

Trust and leadership during COVID-19

Outside of the US, survey respondents are largely happy with how their government is responding to COVID-19. In Australia, 87% think their government’s response has been effective. 84% in the Netherlands, 80% in Germany, and 65% in the UK say the same. Meanwhile, only 49% of American and 53% of French respondents think the government has effectively responded to the pandemic.

A pattern of distrust in the US government continues when you consider government involvement in data collection efforts. 45% of Americans say government involvement makes them less comfortable with the idea of data tracking for COVID-19 containment. Respondents in other countries fall between 26% and 34% when asked the same question.

However, trust in the technology industry is even lower, with social media companies being the worst off. 61% of Americans say they would feel less comfortable with data tracking for COVID-19 if social media companies were involved; many say the same of technology startups (55%) and large and established technology companies (48%).

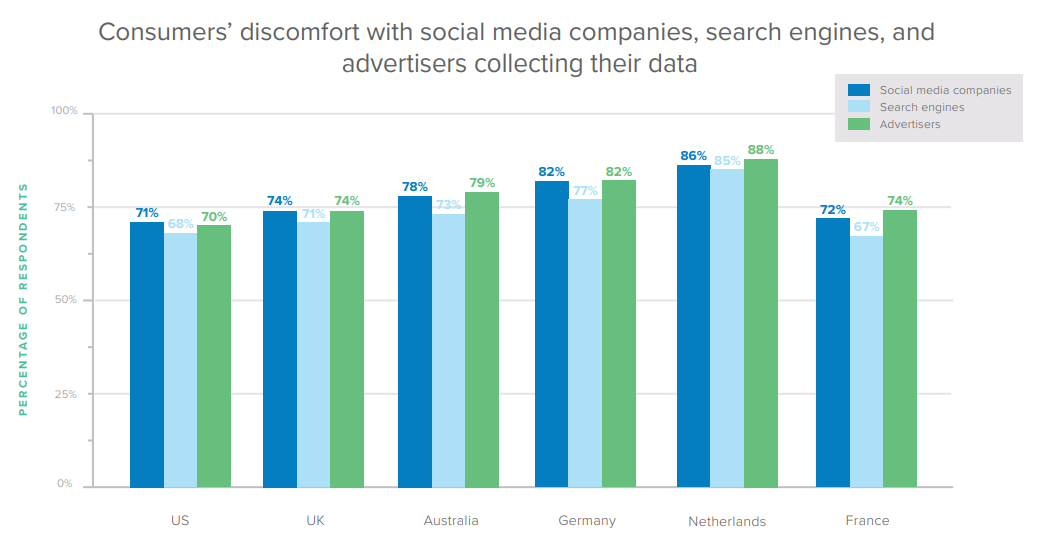

Distrust of social media providers: who watches our Facebook posts more closely, our friends... or Facebook?

Consumer distrust of data collection by social media companies and advertisers is particularly high, which is problematic considering they’re involved in the majority of third party data sharing online. High-profile accusations against social media companies and advertisers likely contribute to this level of distrust.

Across countries surveyed, respondents who think social media companies track more aspects of their data are more uncomfortable with social media companies collecting their data. On the low end, American respondents think social media companies track an average of 5 types of data, and 71% are uncomfortable with it. In the Netherlands, respondents think social media companies track an average of 6 types of data, and 86% are uncomfortable with it.

When it comes to data collection, mistrust of social media closely parallels mistrust of advertisers and search engines.

A New Economic Model? Some Say Data Could be the New Property Right, But Not So Fast

Tech companies typically own the data that is generated by users on their platforms. But in order to give consumers more control over the collection and sale of their data, some politicians have proposed policies that would require organizations to pay consumers for access to their data. Former US presidential candidate Andrew Yang proposed this type of system during his campaign, suggesting that consumers should “receive a share of the economic value generated from [their] data”.3 consumers aren’t buying it.

“Data for dollars:” compensation isn’t enough

We asked global consumers if they’d be more willing to share data with companies if they were financially compensated, and 37% say no. Another 27% are unsure if payment is worth it to sacrifice their data. When it comes to specific types of data, 76% of all respondents are unwilling to sell at least one type of their data at any price. Ultimately, consumers value data privacy more than some extra cash.

Breaking out the results by country, Dutch and German consumers are the least likely to be incentivized to share their data for compensation, with 45% of Dutch consumers and 42% of German consumers unwilling to sell. American and French respondents are the most open to the idea, but still show hesitancies. Nearly 1 in 3 respondents from the US and France (32%) do not find the idea appealing, and another 26% and 27% respectively say they are unsure.

The biggest divergence in opinion can be seen by age. Younger generations are far more willing to share their data at a price.

Of course, everything has a price. We asked consumers if they’d rather sell their data or give it away for free, and more than 90% in all countries surveyed say they would take the cash. But data doesn’t come cheap. For example, 31% of Americans want $100 or more for a company to access their browsing history or social media data. 25% want that same price for their location data.

These price tags don’t bode well for companies trying to make a policy like this work. Facebook, for example, has 2.5 billion users. Paying each of those users $100 in exchange for their location data — not to mention their purchase history, browsing history, etc. — comes out to a whopping $250 billion. This economic model would be even less effective for small businesses who need user data to improve their product but don’t have the resources to pay for it.

Identity Verification is Taking a Toll on Democracy

As governments try to reduce cost and improve accessibility, they are increasingly making services available online. Of course, verifying the identity of a visitor is a critical issue when providing access to government records and services. But there is a tradeoff between security and usability: if the barrier to entry becomes too high, citizens will abandon the process, and possibly give up on the service entirely.

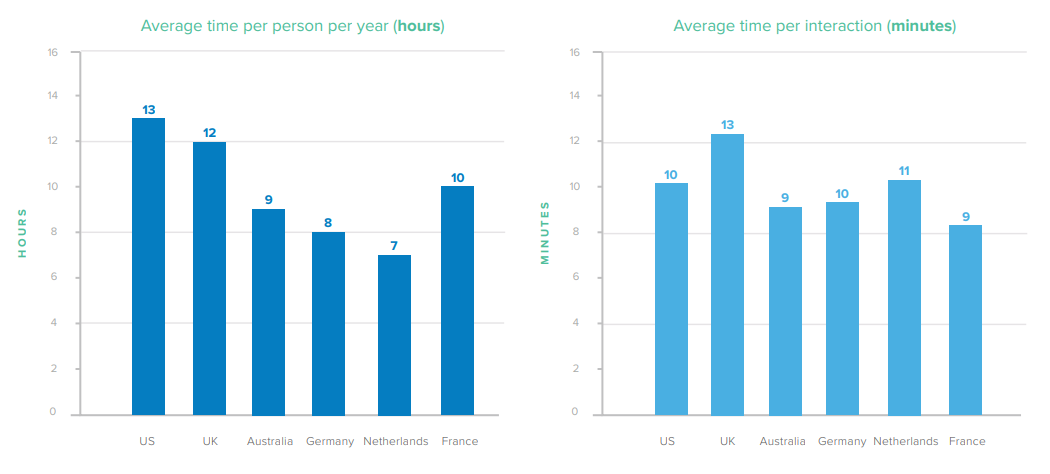

Streamlined online access can free up hours of time

We asked respondents in each country surveyed how long they spend logging in or otherwise proving their identity with a variety of government departments, and on average, they’re spending 12 hours per year. When looking at individual countries, the number ranges from 7 in the Netherlands, to 13 in the US.

The relatively low amount of time each French person spends interacting with different government departments can likely be attributed to the unified Service-Public.fr identity portal. This allows a wide range of functions to be carried out through a single interface. The average French person spends 10 hours per year proving their identity, a 26% improvement over the US.

Implementation of unified identity solutions can save a large amount of time for both governments and the public they serve; if the US achieved the same level of efficiency as France, for example, its population would save nearly 19 million days.

A small barrier so critical, it could affect a national election

While online logins can be taxing on productivity, they are easier to navigate than the requirements of many state voter registration systems.

Each election cycle, we hear stories about the difficulties some determined citizens overcome in order to cast their vote. For some citizens, simply registering to vote can be complex and intimidating, and not every citizen battles through to the end. The complications related to proving one’s identity take their toll on democracy, particularly in the US. Of those Americans not registered to vote, 14% report avoiding doing so because of complications with the registration process. Of those, 39% think it is too time consuming, and 33% feel the process is overwhelming.

What are the implications of 14% of the unregistered population choosing not to register to vote? In 2018, the US had a population of 327 million people.4 With 153 million people registered to vote that year,5 that would leave 101 million people unregistered (excluding minors ineligible to vote).6 If 14% of those unregistered Americans didn’t encounter complications, it would translate to more than 14 million more people voting — a sizable number that could affect the outcome of a national election.

The key to increasing voter participation is to challenge the notion that registering to vote is onerous. Moving to a digital registration system, which many states still do not offer, could speed up the registration process and make it available from anywhere. This would be a big step toward making democracy accessible to everyone.

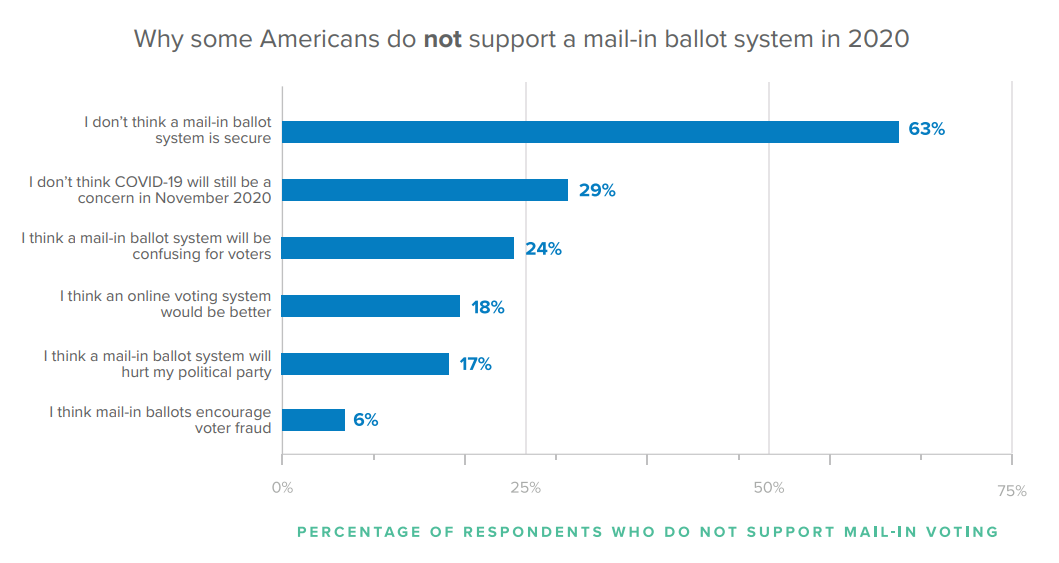

2020 elections and the impact of COVID-19

As the fight against COVID-19 continues, many are wondering how the 2020 election will be impacted. Will crowded polling stations undo the progress we’ve made to slow the spread of COVID-19? How will we ensure every American still has the ability to cast their vote? Is a mail-in ballot system a good solution? The right answer is unclear, but one thing is for certain: steps must be taken to ensure a safe, secure, and inclusive election year.

We asked about the impact of the pandemic on the 2020 US election, and 67% of Americans say they support the use of a mail-in ballot system to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Support for mail-in voting is consistent across generations, with 61% ages 65+ and 77% ages 18-24 onboard.

While some policymakers have pointed to increased voter fraud as a reason to avoid a mail-in ballot system,7 only 6% of Americans against a mail-in ballot system agree. Instead, general security is the top concern.

We asked all US respondents what they thought about the security of different voting systems, and found a consistent theme: every option has its skeptics. 82% say in-person voting is secure, while 65% say the same of mail-in voting. A slight majority of Americans definitely aren’t ready for online voting, with 51% saying it is insecure.

Conclusion

As our lives migrate to the digital realm, our online identity has evolved to become an increasingly robust collection of data about every aspect of our online and offline lives. This data is extremely appealing to companies and governments who wish to use it for a variety of purposes.

Our survey suggests that consumers around the world have only a vague understanding of how much of their data is being tracked, where, when, and by which organizations. But despite this lack of awareness, they’re largely uncomfortable with the idea of companies collecting and selling their data, even when it comes to benevolent causes like tracking the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Okta believes it is important to balance privacy and innovation. Consumers deserve to have control over their data, but at the same time, data is often essential to building new technologies and serving the common good. To strike a balance, organizations around the globe must embrace transparency and help their customers understand how their data is being used.

Methodology

The survey was commissioned by Okta, and carried out by Juniper Research. It was distributed and completed through an online platform.

The survey was carried out using an online panel in two waves, between the dates of 20th and 31st January 2020 and 27th April to 6th May. The survey was a nationally representative sample of the online population aged between 18 and 75 of each of the following countries, in the local language:

- Australia (2,002 respondents in wave 1, 947 in wave 2)

- France (2,000 respondents in wave 1, 973 in wave 2)

- Germany (2,000 respondents in wave 1, 936 in wave 2)

- The Netherlands (2,006 respondents in wave 1, 1,004 in wave 2)

- The United Kingdom (2,218 respondents in wave 1, 979 in wave 2) • The United States (2,013 respondents in wave 1, 923 in wave 2)

Confidence intervals at the 95% confidence level for all countries are ±2.2% for wave 1, and ±3.2% In wave 2. All data was weighted in line with nationally representative proportions.

1 Scott Goodson. “If You’re Not Paying For It, You Become The Product.” Forbes (2012): https://www.forbes.com/sites/marketshare/2012/03/05/if-youre-not-paying-for-it-you-become-the-product/#3c8f06135d6e

2Ryan Nakashima, “Google Tracks your Movements, Like it or Not,” Associated Press (2018): https://apnews.com/828aefab64d4411bac257a07c1af0ecb/AP-Exclusive:-Google-tracks-your-movements,-like-it-or-not

3Regulating Tech Firms in the 21st Century, Yang 2020 (2019): https://www.yang2020.com/blog/regulating-technology-firms-in-the-21st-century/

4“Quick Facts United States,” U.S. Census Bureau (2019): https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045218#PST045218

5“Number of Registered Voters in the United States from 1996-2018,” Statistica (2020): https://www.statista.com/statistics/273743/number-of-registered-voters-in-the-united-states/

6“America’s Children: Key Indicators of Well-Being,” ChildStates.Gov (2019): https://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/demo.asp

7Kathryn Watson, “Trump ramps up attacks against mail-in voting,” CBS News (2020): https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-vote-by-mail-attacks/