Identity is the target

The “Big Store” con

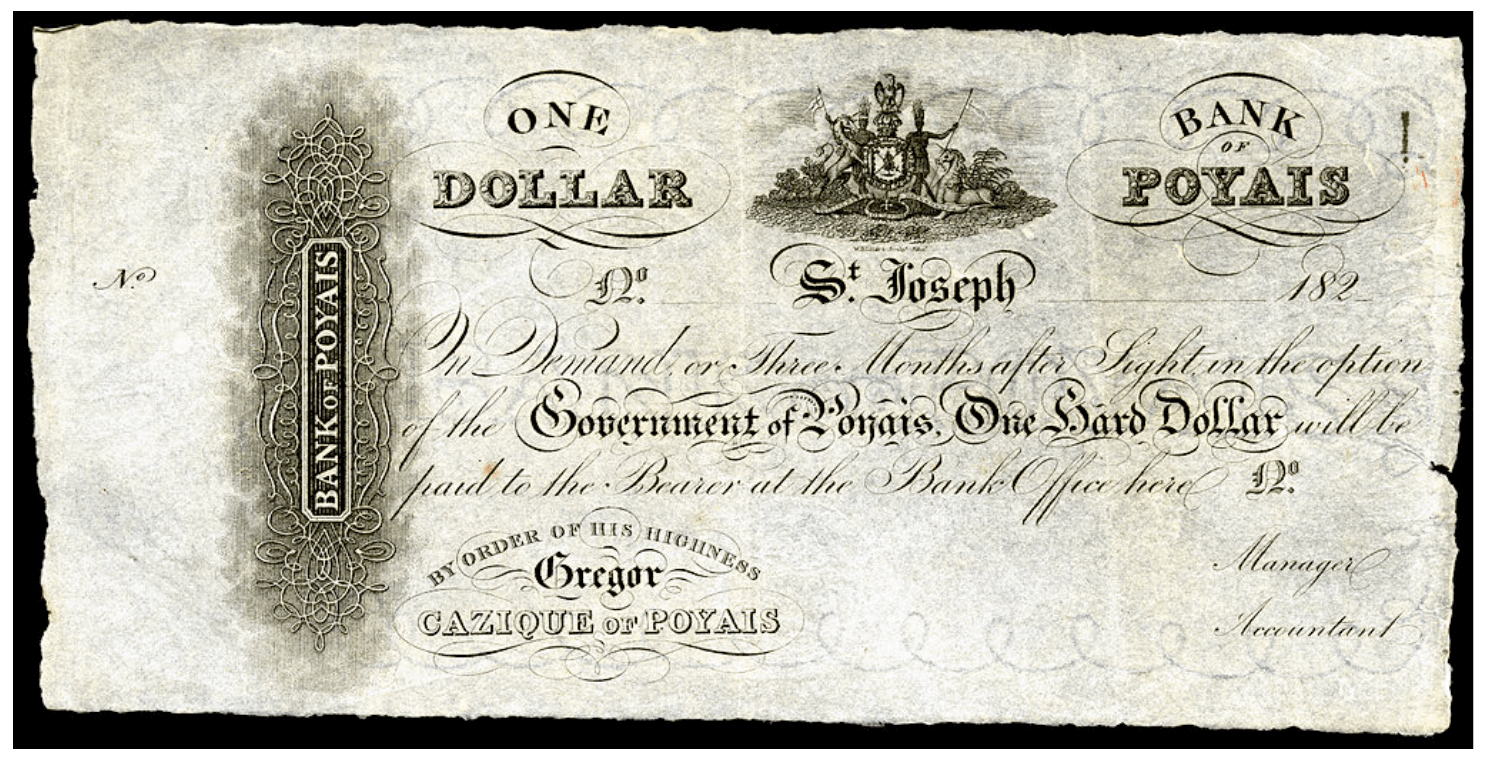

In 1822, a British ship landed on the coast of Honduras carrying 70 settlers eager to start a new life. The passengers of the Honduras Packet had paid handsomely to sail to the bustling town of St Joseph, a settlement of 20,000 people boasting a theater, an opera house, and a domed cathedral. St Joseph was the capital of the remarkable country of Poyais, a land of fertile soil and plentiful game, guaranteeing riches to all who lived there.

When they finally disembarked after crossing the Atlantic, however, the settlers found only jungle and disease. There was no bustling town, no graceful buildings: Poyais was a scam dreamed up by a Scotsman named Gregor MacGregor. Over the next three years, a total of five ships would make the trip. Of the 250 people duped into believing in this mythical place, 180 would perish.

Grifters have names for their cons, such as the “Spanish Prisoner” or the “Pigeon Drop.” MacGregor’s ruthless scheme was a type known as the "Big Store," a scam that requires creating an alternate physical reality that is literally inhabited by its victims. For MacGregor and his accomplices, this meant forging land grant certificates and bank notes, designing uniforms for the imaginary Poyaisian army, setting up fake offices in London, and filling real ships with people sailing to their deaths.

From emigration scams to phishing attacks

The "Big Store" con requires manipulation of physical space, and it’s hard to get all the details right. While “Big Store” cons may show up in the movies — The Sting, for example — they’re rare in real life. Why is this type of con so hard to pull off? Because humans have evolved to assess our surroundings. We pick up on details, even if we're not consciously thinking about them.

Our survival has depended on our noticing predators, even if we can't completely see or hear them. Our brains process thousands of signals, scanning for anomalies. Our “sixth sense” usually tells us when something is off.

But in the digital world, large-scale fraud is easier to pull off. You don’t need to create an entire counterfeit country. And sadly, our evolutionary strengths as humans are actually exploited to become weaknesses.

Gregor MacGregor needed a 165-ton sailing ship for his swindle, but a digital attacker can build a phishing site in minutes. When we assess that website using the same tools we use in physical space, they utterly fail us.

We may have an uncomfortable intuition about a fake office building, but when we get a genuine-looking email from what we think is our university’s IT department, we probably won’t give it a second thought. We may not, for example, scrutinize the link we’re called upon to click before we dutifully provide our bank routing number, as happened to several unfortunates at UMass Boston.

Likewise, if the pixels are good enough, we may not realize that we’re signing into a North Korean phishing site rather than our Apple account. Such was the fate of the Sony Pictures executives who found themselves duped into giving away their Apple credentials.

As the hackers suspected, some of those credentials contained reused passwords that worked for Sony network accounts as well, allowing North Korea to cause $100 million worth of damage to Sony as payback for releasing a movie that Kim Jong Un didn’t like. (We’ll say more about password reuse in a moment.)

Deepfakes

In the age of artificial intelligence, this gets even worse. In February 2024, a young employee at Arup, the multinational engineering firm that built the Sydney Opera House, unwittingly transferred $25M to a group of attackers.

The employee received an email requesting a secret transfer and became suspicious. A video call involving “multiple participants” (the exact number hasn’t been disclosed), many of whom he recognized, convinced him the transaction was above board.

Imagine being that young man being told by not one or even two but a roomful of colleagues to transfer the money. Did he have a reason to believe that they were all fake?

What makes the “Big Store” con so hard is what makes deepfake fraud so brutally effective. We’re hardwired to recognize others of our species. Facial recognition is part of our DNA. When we don’t have a face to see, we can identify someone from their voice, their body, and even their scent.

We don’t question our ability to recognize one another in the physical world and, as a result, we bring the same hubris into the digital world. Against a sufficiently clever adversary, we don’t stand a chance.

Take the case of a Brooklyn couple, Robin and Steve, who received a call in the middle of the night in which they had to listen to Steve’s mother’s panicked voice before a man told them, “I’ve got a gun to your mom’s head, and I’m gonna blow her brains out if you don’t do exactly what I say.” He asked for $500 over Venmo. Who wouldn’t pay such a small sum if they thought their mother might die? When Robin and Steve finally contacted his mother, she was safe at home. There was no kidnapper.

This kind of attack exploits another of our commendable human qualities: our desire to protect those we love. Whatever skepticism might have protected us in a calmer moment is swept away by the rush of emotions we feel when faced with the need to protect our loved ones.

What’s worse: Deepfake attacks are easy, and getting easier. As always, YouTube is there to help. I followed a seven-minute Youtube tutorial and cloned my voice convincingly.

Password reuse and credential stuffing

There are devastating attacks in the digital realm with no physical analogs. For example, we regularly read about breaches that result in hundreds of millions of stolen passwords. For Yahoo in 2013, it was 3 billion passwords.

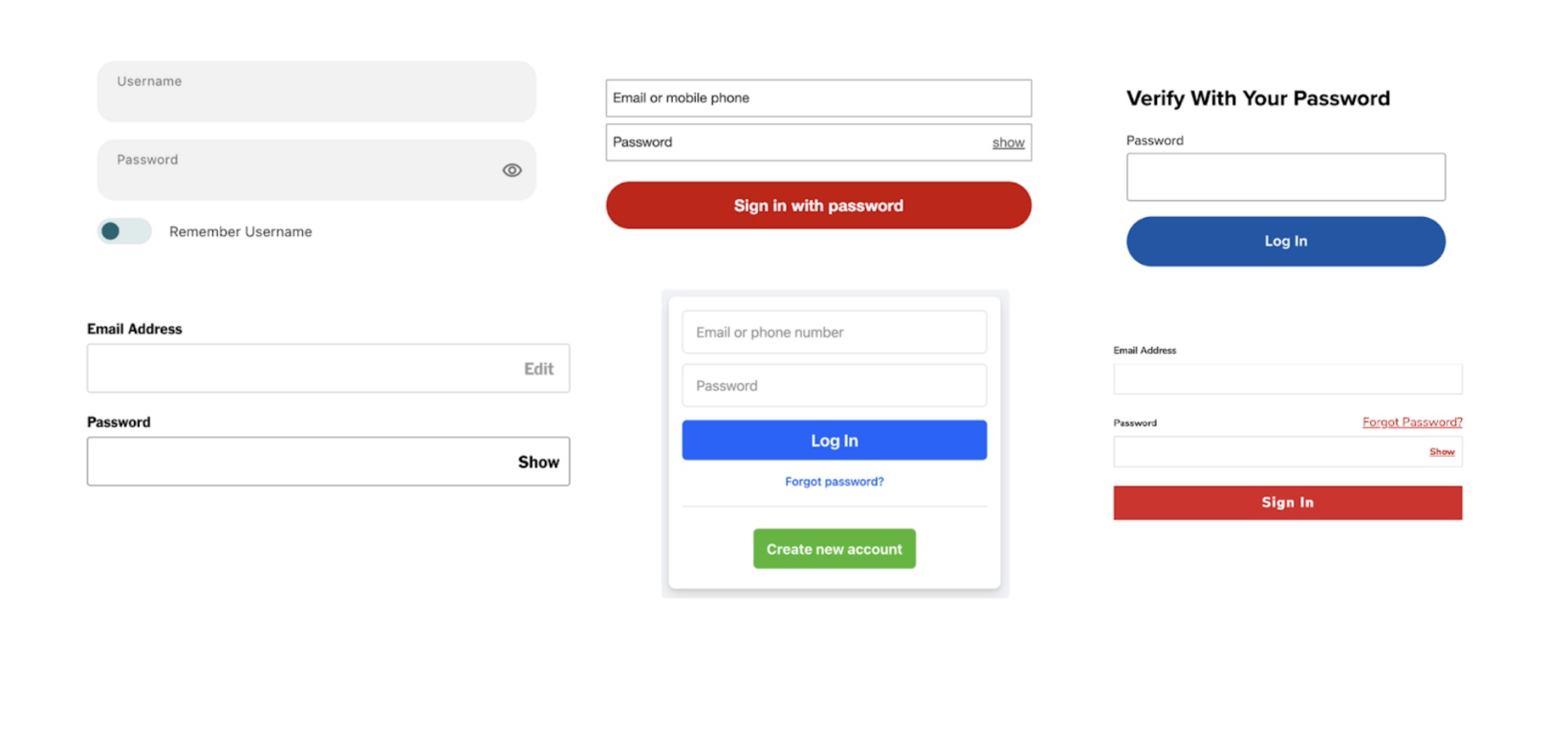

Some of those passwords were reused on other sites, which allowed the attacker to do a credential-stuffing attack: if they’ve stolen [email protected]’s password, they try the password with [email protected] as the username on as many sites as possible. If the password was reused, then bingo — they’re in!

We may know that reusing passwords is a bad idea, but needing to create (and somehow recall) a different password for every website we use is also a bad idea. We can wag our fingers at people who reuse passwords, but password reuse is a practical and human way of trying to solve the problem of cognitive overload. Unfortunately for us, this plays right into the attackers’ hands.

Attackers focus on Identity

These attacks all have two things in common: 1) They target Identity, and 2) They’re far easier to execute than their physical counterparts. As we’ve seen, attacks against Identity hit us where it hurts. Fortunately, Okta has solutions to the challenges of Identity protection.

Multi-factor authentication

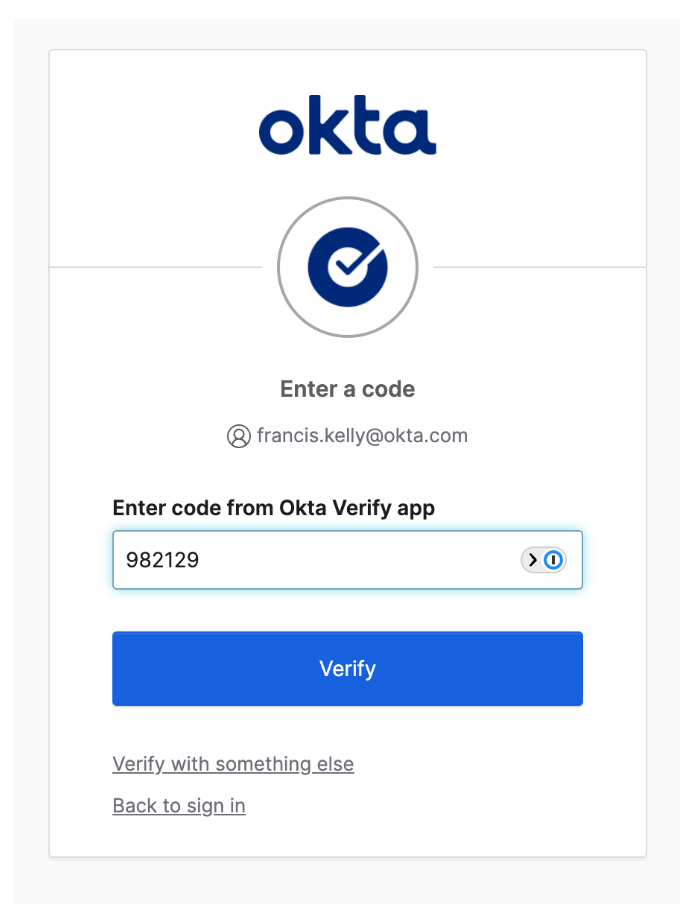

Multi-factor authentication (MFA), a core Okta product offering, is a great place to start. OWASP advises: MFA is by far the best defense against the majority of password-related attacks, including credential stuffing and password spraying.

A company that suffers a data breach but has MFA in place still has one line of defense left to protect customers whose data was stolen. Likewise, a stolen, reused password will be ineffective at any site requiring a second factor.

Smart companies also protect access to applications their employees use. For example, if employees only conduct business using the company’s videoconferencing account and that account requires authentication via Okta, a deepfake video scam becomes much harder to pull off.

Phishing-resistant factors

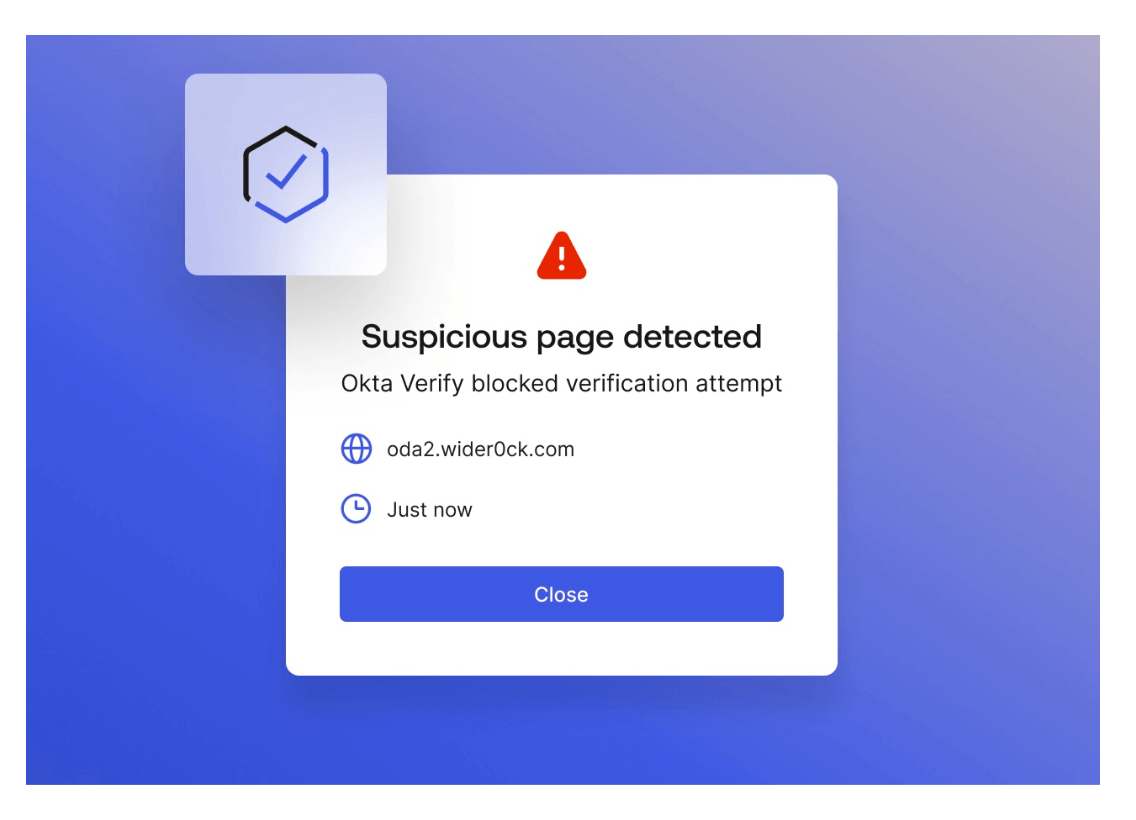

As secure as MFA is, it’s not perfect. Determined attackers can phish second factor along with a password. Okta FastPass offers phishing-resistant MFA to combat this. As individuals, we might be fooled by a phishing site. But a phishing-resistant second factor relies on cryptographic protocols that are almost impossible to circumvent.

Moving away from passwords

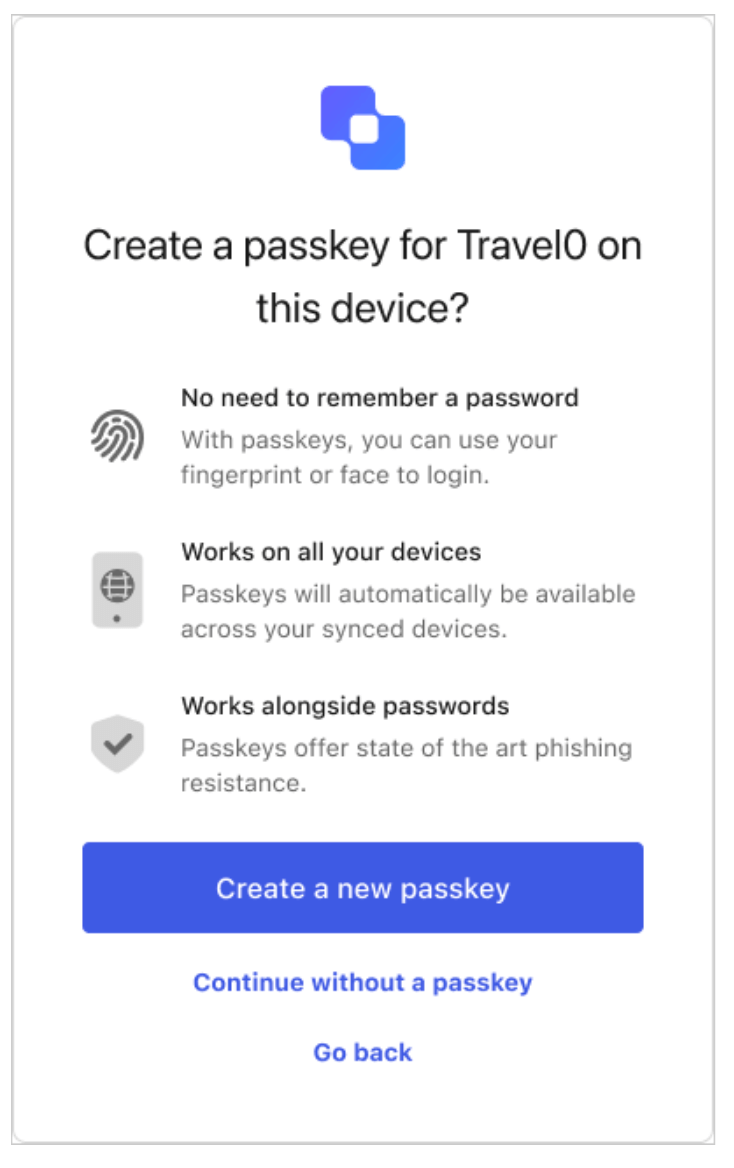

Finally, customers can stop using passwords altogether. Okta FastPass allows users to authenticate to any app within Okta without a password. Likewise, users can adopt passkeys with any website that supports them — which is increasingly common. Passkeys basically allow the user to register their device with a website. Each time the user registers with a website, their device (such as their phone) creates what’s known as a “key pair.” The key pair consists of a private key that’s kept secret on the phone and a public key that’s sent to the website. Through the magic of public key cryptography, the key pair allows the user to log in to the website without ever using a password.

A long way to go

Human beings are capable of trusting and, therefore, are capable of being deceived. Fraud has always existed. Over the millennia of our existence, we’ve developed at least some skill in telling truth from falsehood in the physical world.

In the digital world, however, we have a long way to go. This is an unhappy truth to confront, but even if human ingenuity doesn’t innately protect us from online fraud, it’s allowed us to build the tools that will. Learn more about how to protect against evolving digital threats by going passwordless with Okta.