Understanding usability may be your missing evaluator when establishing a product’s value. Like tech stacks, a human’s ability to process information affects product performance. Usability principles streamline how users process information and evaluate how useful a product is.

Establishing product value

When thinking about adding more value to a product, we often begin by exploring new features or enhancements to existing ones. What stumps us when we launch a new feature is when it doesn't create the intended impact. Even more challenging is when an enterprise product experiences a drop in user satisfaction. Evaluating usability may be a missing factor in helping predict success.

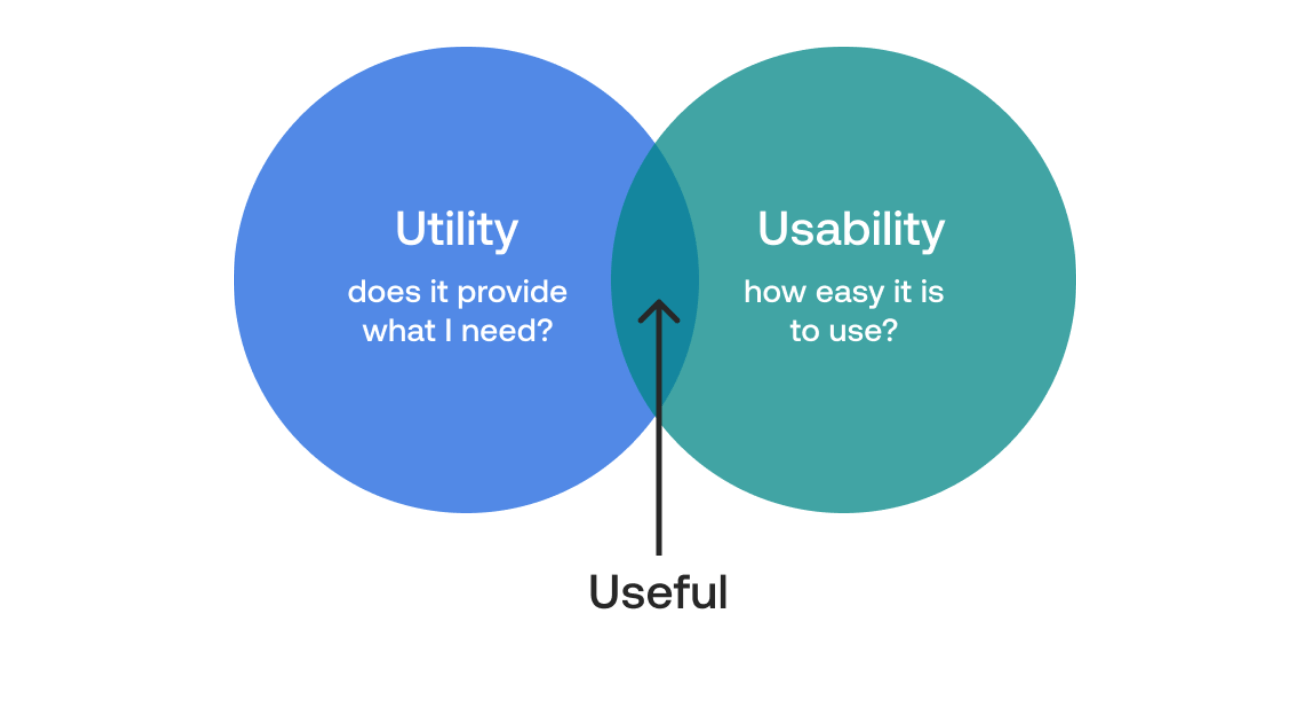

Users establish a product's usefulness using two equal factors: utility and usability. Utility is whether it provides the features needed, and usability is how easy and pleasant these features are.

UX industry leader Jakob Nielsen introduced this approach to establish usefulness and highlight how usability is a crucial quality attribute for any business that builds digital products. The bottom line is that the amount of time users may spend being lost on your product or trying to decipher technical documentation decreases productivity and revenue.

Evaluating usability

Usability is often confused with user experience. While it is a part of the overall user experience, it focuses on the user's ability to learn with minimal errors and retain information efficiently. Similar to technology, human brains have a limit to the amount of data they can hold before experiencing slower processing times.

Improvements to the user interface can address usability issues, but design psychology is key to minimizing user fatigue. While it is most common to think about it during the design phase of a project, it should be evaluated throughout all steps of the product development lifecycle. You can utilize numerous design psychology principles along the way, but here are a few that can be specifically applied to earlier stages of product design and development.

Hick’s law

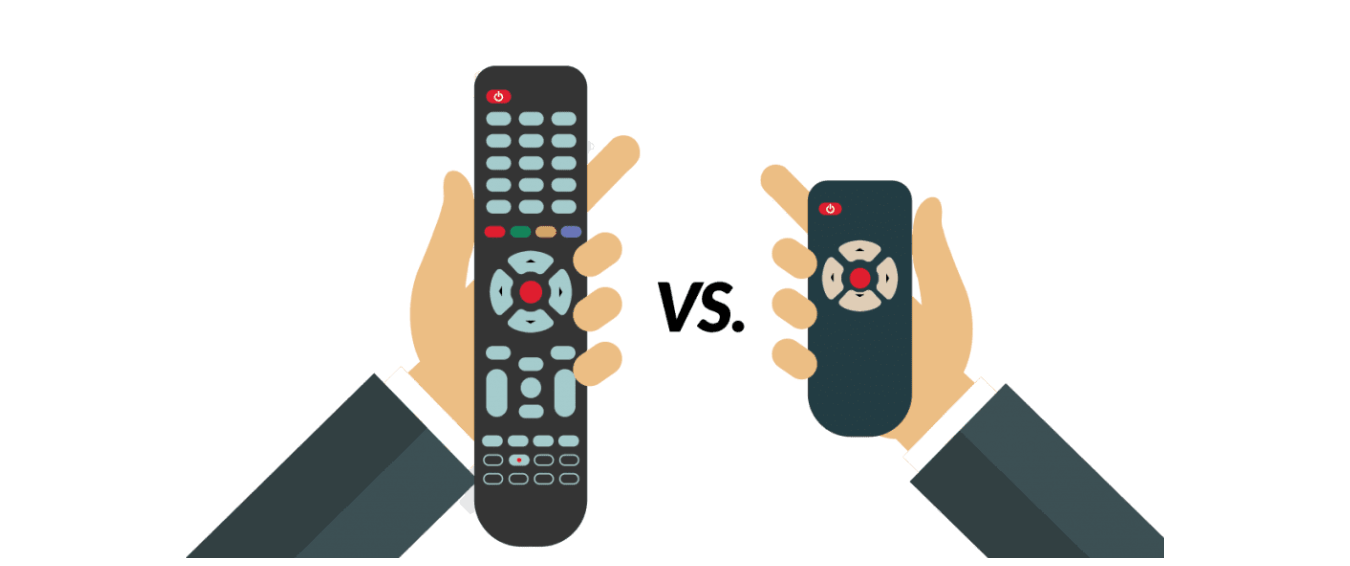

The core of Hick’s law is centered around clarity. It predicts that the number and complexity of choices available to a person will increase the time it takes them to decide. While your first instinct may be to minimize having users go through multiple screens to complete the steps in a process, you may actually hinder their ability to decide because there are too many choices to understand and evaluate. Teams may start with a minimum viable product (MVP) but continue to build on top of it to the point that the cognitive load required of the user becomes overwhelming.

from Hick's Law - The Laws of UX

Doherty Threshold

In today’s digital world, we can all relate to feeling frustrated when we’re waiting for a computer to complete a task. We start clicking around, maybe even refreshing the page a few times, because how could it take more than a few seconds? That is the basis for the Doherty Threshold, which states that productivity increases when a computer and its users interact simultaneously. It is another example of how ensuring a user doesn’t have too many choices at once can equalize the processing time between technology and the human brain.

If a system needs time to process a large file or dataset, make sure you communicate this visually to the user. You can display progress bars or processing animations so they aren’t left guessing if something is working.

Tesler’s Law

Tesler’s Law states that there is a certain amount of complexity with any system that can’t be “designed away.” The benefit of Tesler’s Law is that, when the burden of understanding complexity isn’t put on the user, they actually start to perform more complex tasks because they’re not spending their time trying to figure out how to use a system.

This is why understanding user mental models is essential. A process may be very complex, but if it aligns with how the user expects it to perform, it’s not perceived as complex or difficult to use.

These three principles support how evaluating a problem through a usability lens can provide new insights into how a user may establish a product's usefulness. Not all design psychology principles apply to every scenario, and familiarizing yourself with common UX ones can help you identify which ones best fit your project.

The usability/utility quadrant

So how can a team evaluate usefulness? A fast and effective method is utilizing a quadrant map. It is the perfect tool for engineering, product, and design (EPD) to evaluate if a product or feature skews toward the “total waste” quadrant or when you’ve hit the “useful” quadrant.