Executive Summary

At the current pace of acceleration in agentic AI, it no longer seems prophetic to say that before too long, there will be more AI agents connecting to production applications and data than human users.

There will be profound implications for the workplace - with some estimates that half of the white collar workforce may not be employed within five years. There are also profound implications for cybersecurity.

Agentic AI presents novel risks, such as prompt injection attacks, in which AI agents are effectively “social engineered” into taking action on behalf of an attacker after being exposed to untrusted input.

As an identity company, Okta’s larger and more immediate concern is how agentic AI adds to the attack surface of every organization from an authentication and authorization perspective. We can reliably expect that attackers will discover and abuse the innumerable service account passwords and static API keys developers are generating in order to grant AI agents access to corporate resources. We can also reliably expect that the broad authorization granted to AI agents will exacerbate the potential data loss from the compromise of any given account.

This document is intended as a guide to service providers, organizations and developers experimenting with agentic AI with a view to building production applications.

The role AI plays in identity debt

Identity debt accumulates when shared, static secrets are allowed to accumulate over time in a system. A secret is shared when it’s known or stored by more than one user or in more than one place. A secret is static when it is long-lived, and goes for long periods of time without being rotated.

Agentic AI, our research found, is contributing to an acceleration in this buildup of identity debt. Organizations should rely on enterprise-grade methods of authorizing a client (AI application) to act on a user’s behalf in a protected resource (apps and data).

Our research found the opposite. The most commonly used methods of authorizing an AI agent’s access to functions and data in SaaS apps, code repositories, databases and other resources result in the exposure of highly privileged secrets.

The table on the following page assesses the security properties of various approaches to authorization.

Agentic plugins: the forerunners to MCP

A study of Copilot plugins

Our research found that the majority of the machine-to-machine authentication methods used to connect Al agents to protected resources (enterprise apps and data) use forms of authentication that aren't fit for purpose in production environments, with little to no control over authorization.

To illustrate, we assessed the available authentication methods made available for allowing Microsoft Copilot Al agents to access some of the most sensitive data in the enterprise: security applications.

Copilot is among the world's dominant general-purpose Al assistants. Microsoft offers the ability to create "plugins" for Microsoft Copilot to expose the features of third-party security apps to Microsoft applications (under the brand "Microsoft Security Copilot"). Each Microsoft Security Copilot plugin is configured in a YAML or JSON file (a plugin manifest) that describes what tools in the external service are available to the Copilot agent.

Using these services:

- Microsoft Copilot acts as the host application

- The tools and data of security apps, such as Splunk, SentinelOne, Forescout or Cyberark, are protected resources.

A mutual customer (of both services) must first authorize Copilot to access protected resources on their behalf. This requires the customer to provide Copilot with credentials (passwords, API keys or the Client ID and Client Secret in an OAuth flow), which are stored at-rest on Microsoft servers. The available schemes are listed in the table below.

Security Copilot supports several schemes for authenticating plugins:

Figure 2: Authentication options for Microsoft Security Copilot. Source: Microsoft

Figure 2: Authentication options for Microsoft Security Copilot. Source: Microsoft

When a user prompts Copilot to use a protected resource, the Copilot Al analyzes the request and determines which plugin advertises the relevant "skill" (as defined in the plugin manifest) to draw from. Copilot then uses the stored credentials to make an authenticated API call to the third-party application, which retrieves the data or performs an action and returns a result back to Copilot. We sought to understand what authentication methods were used to connect these protected resources (security applications) to Microsoft Copilot. 5

From our analysis of the third-party plugin manifests published on GitHub, we found:

- 20% support Basic Authentication

- 75% support the ApiKey method

- 5% support an OAuth2 flow

The risks associated with using a Copilot AI plugin hinge largely on (a) thischoice of authentication method and (b) the scope of access provided to the agent.

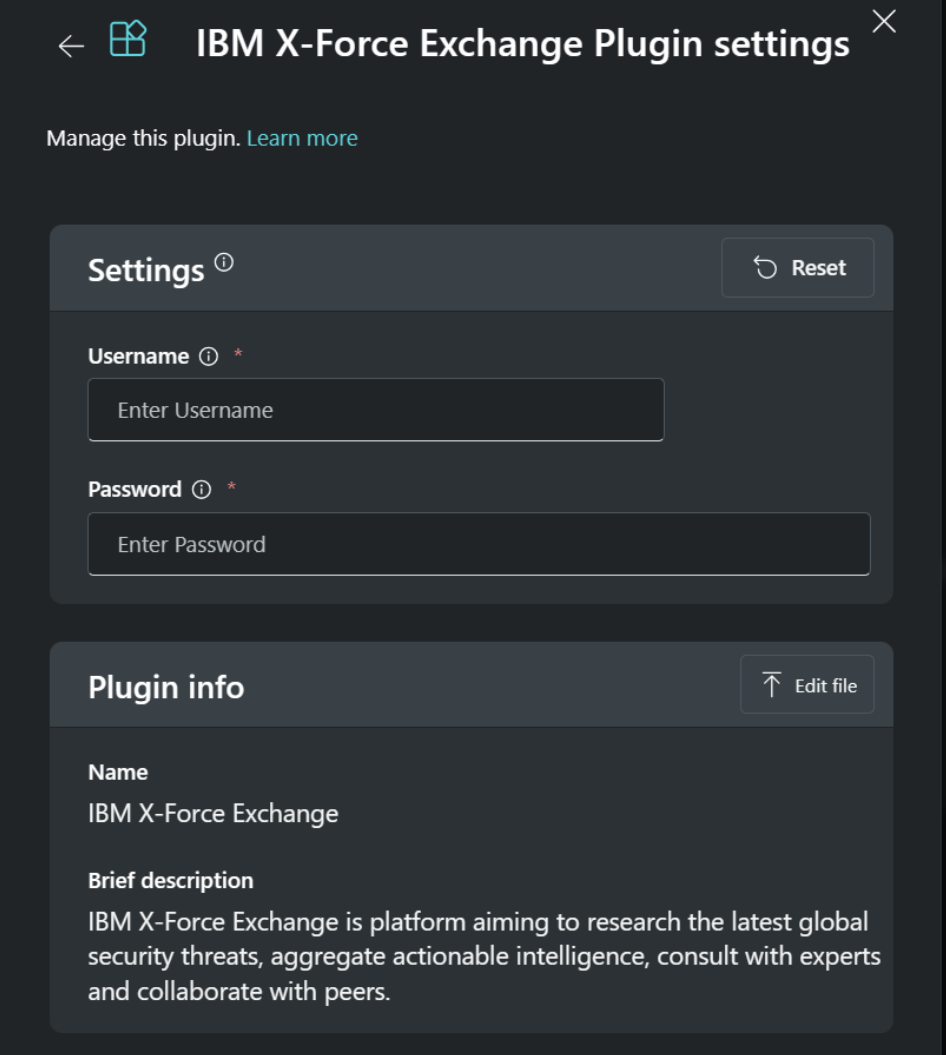

Basic Authentication

Using Basic Authentication, administrators must create a service account in the third-party application and upload the username and password to Microsoft servers. Copilot then sends the username and password in the header of every request to the security app (whenever Copilot selects that tool based on a user prompt.)

Figure 3 and 4: Screenshots from Microsoft Security Plugin Help Documentation

Figure 3 and 4: Screenshots from Microsoft Security Plugin Help Documentation

By definition, user or service accounts configured to allow an Al agent to access resources using the http:basic scheme (basic authentication) cannot support multifactor authentication.

Customers using this scheme must by consequence expose user or service accounts - which are often scoped for broad access to sensitive data - to credential stuffing and password spray attacks.

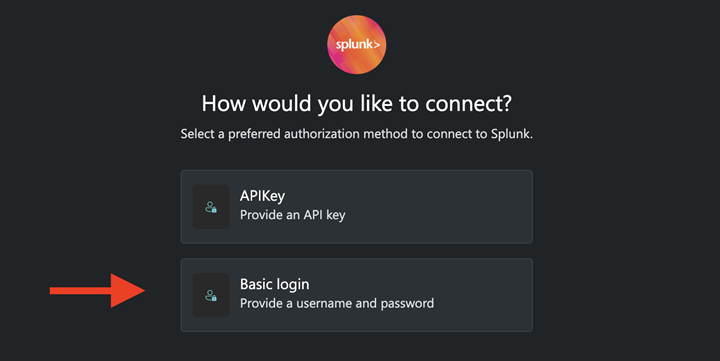

APIKey

Three in four Microsoft Security Copilot plugins can be authorized using the APIKey method.

During configuration, administrators create a long-lived API token in the protected resource, which is typically created in the context of a user or service account, and manually upload the API token to Microsoft servers. Copilot sends the API token in the header of every HTTP request it makes to the protected resource (that is, whenever Copilot selects that security tool based on a user prompt.)

Static API keys offers several benefits over basic authentication:

- API keys are better suited to machine-to-machine flows. Each unique API token can often be configured to expire after inactivity or a set duration. Revocation of the key doesn't have any impact on the user or service account that created it.

- Access to the service account used to create the API token can now be protected using Multifactor Authentication.

- Administrators are more likely to limit the "scope" of what an API token can be used to read or modify, as compared with the permissions of a service account used for basic authentication.

The residual risks are that these API tokens are typically long-lived. API keys are routinely checked into source control systems. API keys are routinely stored in logs when set as query parameters. Occasionally API keys are saved in text files on developer workstation, ready for collection by the next generic infostealer that infects the device.

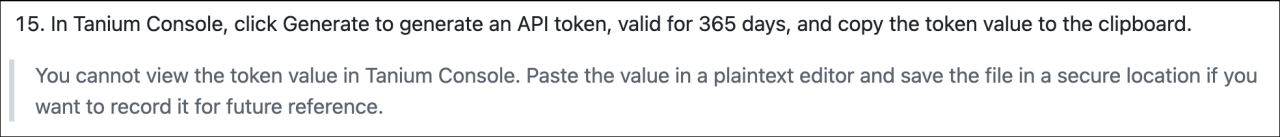

Figure 5: Access to the token referenced in this Copilot plugin provides access to data about all devices in an organization.

Figure 5: Access to the token referenced in this Copilot plugin provides access to data about all devices in an organization.

Static API tokens are highly valued by attackers, and the first thing many attackers search for after compromising a system. Once intercepted, these tokens are typically valid for long periods of time, making them ideal candidates for resale in online markets.

Static API tokens also present availability risks, at least when compared to temporary tokens created in OAuth flows, as static tokens tend to be created in the context of a user rather than an application.

In many cases, if the user or service account that created the token is deleted or deprovisioned, the token is deleted with it, and breaks whatever M2M integration it glued together.

OAuth2

The small remainder of Microsoft Security Copilot plugins appear to use enterprise-grade OAuth2 flows.

In these schemes, a client ID and client secret (shared with Microsoft) are exchanged with an authorization server to obtain a short-lived access token, which is independently validated by the resource server.

If these flows were created in Okta, the resulting access tokens can be IP- constrained (only valid from a configured IP range) and client-constrained (only valid from the client that requested it). Scopes are set at the service application level, not at the user level, which means that administrators do not accidentally disable machine-to-machine integrations when an administrative account or service account is deprovisioned.

While it is disappointing to observe that so few Copilot agents are designed for enterprise-grade authentication, in many respects these choices are a reflection of the existing authentication methods made available by the security apps. In the context of integrating with a single proprietary Al tool, these security vendors were evidently not prepared to invest in updating their available authentication methods.

But what if, instead of writing plugin manifests for every Al application, developers could build a single server to an industry standard supported by all flavours of Al application?

Enter Model Context Protocol.

Modelling threats to Model Context Protocol

If you're a developer of enterprise apps, the economics of having to write a new custom connector (such as a Microsoft Copilot plugin) for every other flavour of Al model is far from desirable.

Service providers would prefer to declare from the outset what data and tools the company is willing to share with any Al model, define the conditions under these resources are exposed, define how customers should authorize the access, and allowlist the Al applications that can access these resources.

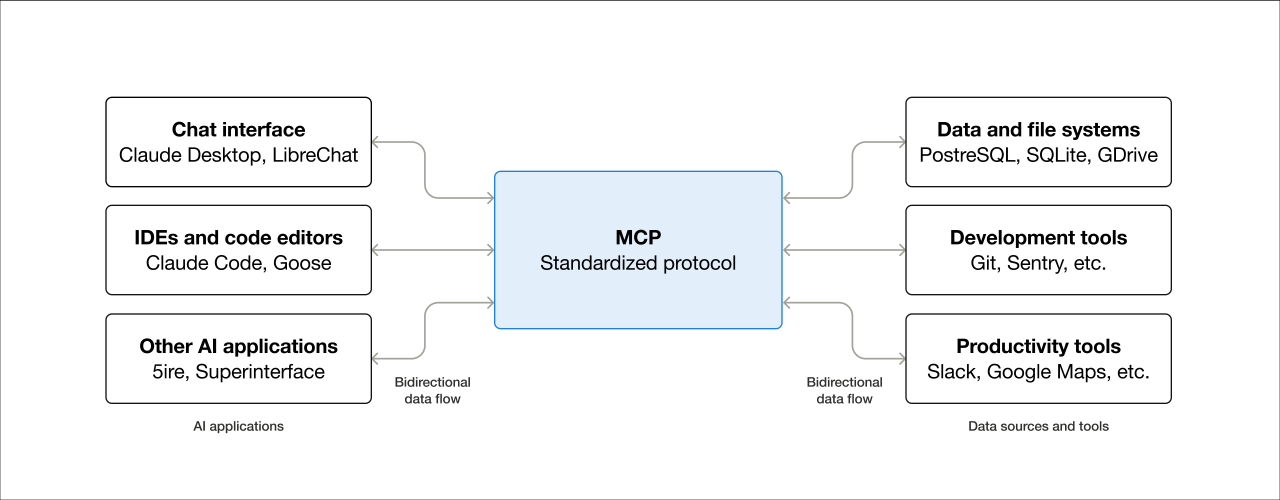

For this reason, the momentum in agentic Al is now building around Model Context Protocol (MCP). MCP is a standardized interface for connecting Al applications (hosts) to enterprise services as diverse as cloud platforms, SaaS applications, code repositories, databases and even payment services. MCP's client-server architecture allows for the "plug and play" of Al applications to the data sources and tools that provide them context.

In the enterprise, MCP promises an ability to:

- Determine what enterprise-owned data sources and tools are available,

- Allow agentic Al applications to access data sources and tools from multiple applications, without cross-contamination of data,

- Lower the cost of experimenting with different Al applications that access those data sources and tools.

Figure 6: A visual description of Model Context Protocol. Source: modelcontextprotocol.io

Figure 6: A visual description of Model Context Protocol. Source: modelcontextprotocol.io

MCP servers can be deployed locally or remotely. This choice of deployment model for any given use case has a significant bearing on the resulting threat model.

The scope of our research was constrained to understanding how Al applications (hosts), MCP clients and MCP servers handle credentials. The core components we assessed were:

- MCP hosts: Al applications, including Integrated Development Environments (IDEs) like Cursor, VS Code or Claude, which require access to the tools advertised by MCP servers.

- MCP clients: The multiple clients an MCP host uses to communicate with a paired MCP server.

- MCP servers: MCP servers advertise the tools and resources available in an external service and make API calls to these services.

Local MCP servers

The MCP model is especially attractive for software development use cases.

Software engineers using Al-enabled IDEs like Cursor and VS Code can build code locally, while drawing on the assistance of remote Al models to make suggestions as the developer writes code.

Anthropic makes its Claude Al agent available for local deployment as "Claude Desktop". Claude Desktop is a locally-deployed MacOS and Windows client and an alternative to accessing Anthropic's Al models via the browser. One advantage to local MCP servers is that clients can interact with both a remote Al model and local files (docs, images etc).

These desktop applications often need to authenticate to both the LLM (this typically requires an API key) and to remote data sources (such as code repositories, which require a Personal Access Token).

When a user launches the host application, such as Claude or Cursor, the MCP client spawns an MCP server and passes the server any credentials (API keys, database credentials, passwords, OAuth client secrets etc) required for operation from a local configuration file, including those credentials the MCP server requires for access to remote services.

If the MCP server is designed for access to Github resources, for example, the host requires a Github Personal Access Token (PAT) to be available in the local configuration file. The server will error out if the Github PAT is not provided.

Figure 7: An MCP server used for accessing GitHub resources errors out if a PAT is not supplied in the configuration file.

Figure 7: An MCP server used for accessing GitHub resources errors out if a PAT is not supplied in the configuration file.

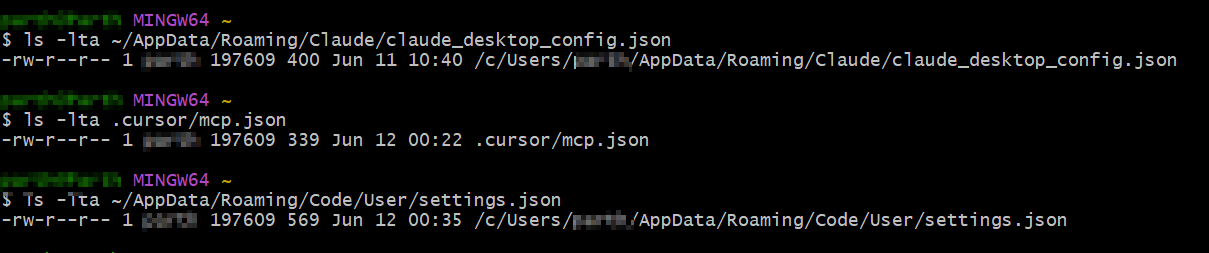

The location of configuration files for three of the most popular development applications that use Al are provided below:

| App | Local Configuration File | Default Locations |

|---|---|---|

| Claude Desktop | claude_desktop_config.json | Default location on MacOS: ~/Library/Application Support/Claude/ Default location on Windows: ~/AppData/Roaming/Claude |

| Cursor | mcp.json | Default location when used globally (all OS): ~/.cursor/mcp.json If an MCP server is only available to a specific project, the configuration file is placed in the project directory. |

| VS Code | settings.json | Default location on MacOS: ~/Library/Application Support/Code/User/ Default location on Windows: ~/AppData/Roaming/Code/User |

Research by Keith Hoodlet at Trail of Bits noted the risks of storing static API keys in plaintext in these files, and cited examples of where these files were world-readable (i.e. able to be accessed by any user of the system).

Extending this research, we assessed the default configuration files for Claude Desktop, Cursor and VS Code, and observed the same permissions.

Figure 8: Default permissions for Claude, Cursor and vs code configuration files.

Figure 8: Default permissions for Claude, Cursor and vs code configuration files.

The same permissions appear to apply to configuration files included in numerous official MCP server implementations that are described as "production-ready", and for just about all the community integrations developed by third parties, which are not endorsed by the service providers in question.

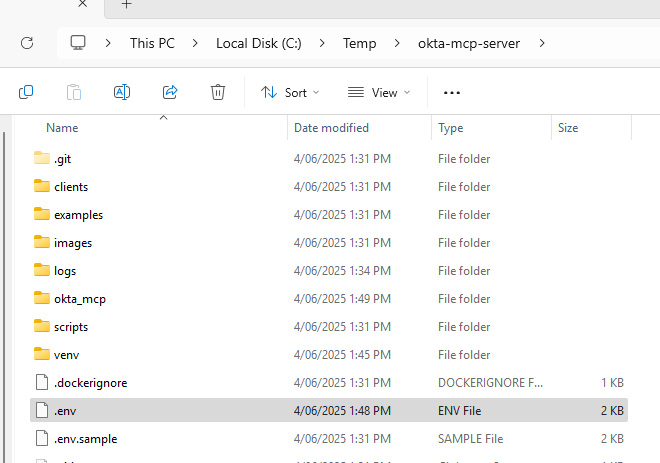

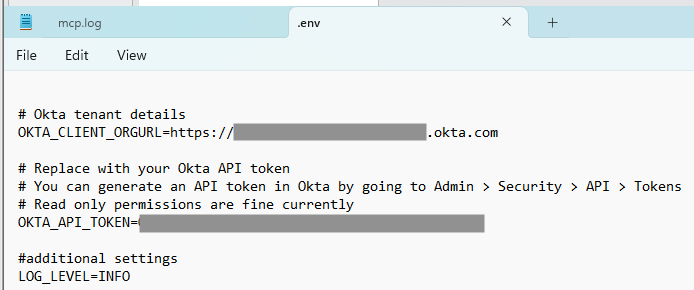

Figure 9 and 10: An unofficial "community integration" asks Okta customers to upload an SSWS token to a local configuration file.

Figure 9 and 10: An unofficial "community integration" asks Okta customers to upload an SSWS token to a local configuration file.

Any threat modelling should anticipate that the vast majority of MCP servers shared to date are not endorsed, which leads to heightened risks around developer use of rogue MCP servers.

A preliminary VirusTotal analysis of MCP servers uploaded to GitHub [2] discovered that 8% of them were suspicious. An undisclosed number of those included code that attempts to identify secrets (keys, passwords etc) in prompts and posts them to external endpoints.

The insecure storage of API keys presents a range of risks, each of which are explored below.

Risks associated with insecure storage of API keysKeys uploaded to software repositories

Keys uploaded to software repositories

Most documentation for local MCP server implementations do not warn developers or other users about the risks of storing plaintext credentials for production resources in configuration files. It is assumed that developers will securely vault the credentials, such that the configuration file only references a credential stored in a secure location.

We observed some scenarios in which the MCP configuration was not able to fetch the credential at runtime unless it was stored in plaintext in the configuration file.

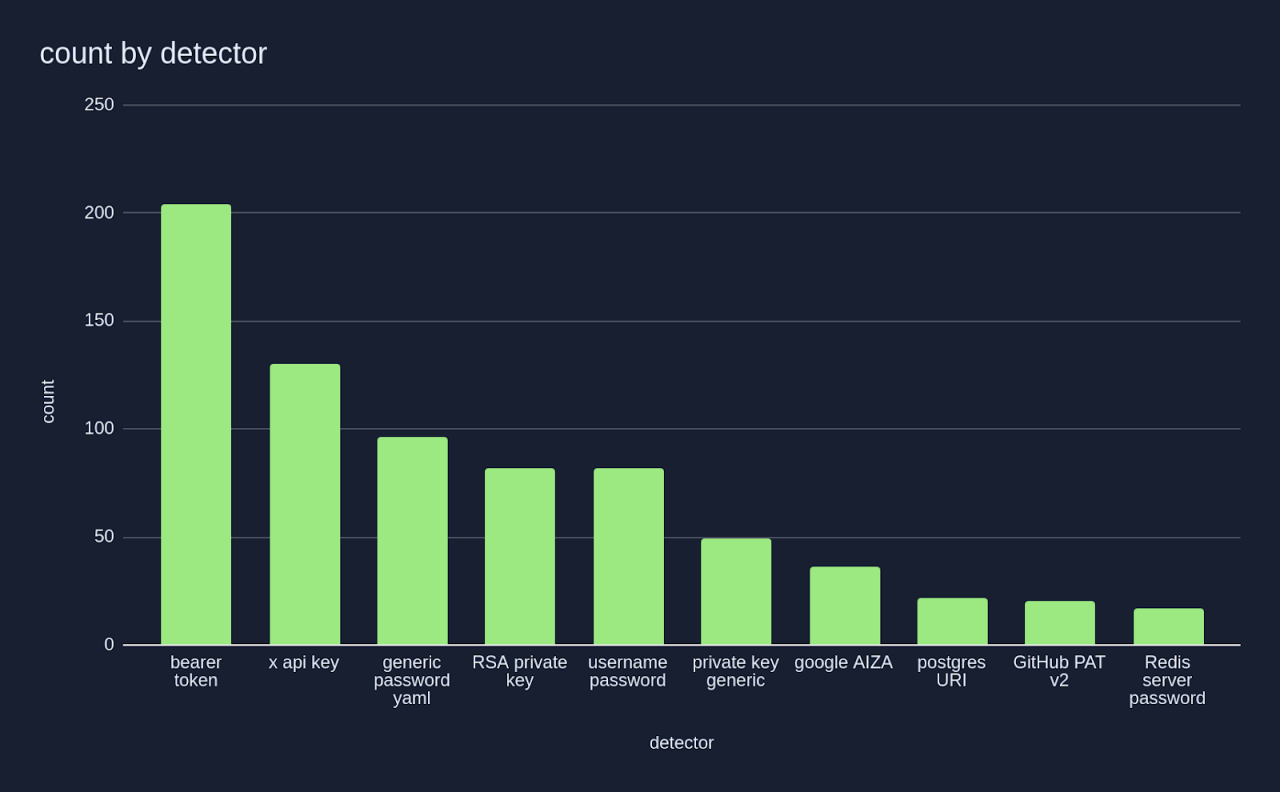

- Research by Gaetan Ferry at GitGuardian of repositories cloned from the unofficial Smithery.ai MCP server registry found 202 examples that contained at least one secret (5.2% of all repositories scanned). Static API tokens (see "x-api-key") featured prominently[3].

Source: “A look into the secrets of MCP”, GitGuardian, April 2025

Source: “A look into the secrets of MCP”, GitGuardian, April 2025

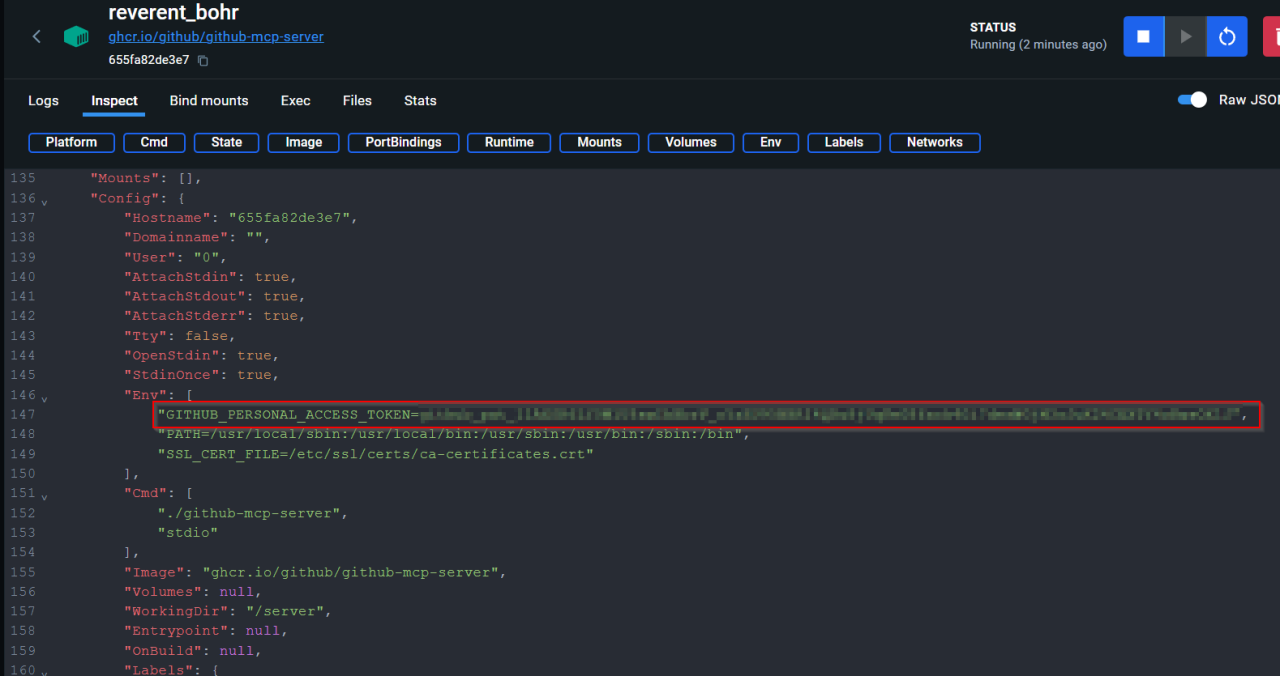

Keys are exposed in container metadata

Running MCP servers in containers shifts rather than mitigates the issue. The secret must be passed to the container in a format that the MCP server supports.

Reviewing container configuration provides a direct reference to a cleartext secret - whether that's in the form of a file on the host, or from being able to identify the relevant environment variables in a container which can be exposed by running docker inspect, a command line tool that allows for inspection of docker resources.

Figure 11: A GitHub Personal Access Token exposed in container metadata.

Figure 11: A GitHub Personal Access Token exposed in container metadata.

Keys accessed by malware

Commodity infostealer malware is designed to locate specific paths and file types where credentials are stored.

For example:

- Windows infostealers, such as Vidar Stealer, will search for secrets stored at ~\AppData\Roaming

- MacOS infostealers, such as Atomic Stealer, search for secrets stored at ~/Library/Application Support

It is highly likely that the insecure storage of static API tokens in these locations will result in impactful events. Where a session token stored in this location provides a brief window of time in which an attacker can gain user- level access to a resource, a static API Token provides persistent access to organization-wide resources.

Keys backed up to external systems

Keys are exposed in backup volumes if administrators fail to exclude sensitive folders (such as ~\AppData\Roaming on Windows or ~/Library/Application Support on MacOS).

Workstations shared between multiple users

Given configuration files were found to be world-readable, keys stored by one user on a shared device are also accessible to other users that log-in to the same device.

Secure alternatives for local credential storage

The recommendations section of this document outlines tactical solutions that minimize these credential storage risks.

Alternatively, organizations experimenting with MCP can take a "secure by design" approach and use solutions developed with these threats in mind.

Take the Auth0 MCP server, for example [4]. The Autho MCP server offers administrators the ability to authorize access to Autho resources from local Claude Desktop, Cursor or Windsurf applications using the OAuth 2.0 Device Code Authorization flow.

Figure 12: Authentication flow using Autho MCP Server

Figure 12: Authentication flow using Autho MCP Server

By default, credentials are stored in the MacOS Keychain after authentication and are removed from the keychain whenever the administrator signs out of the MCP server.

Further, no scopes are selected by default: an administrative user is asked to select them.

Remote MCP servers

A remote MCP server operates as a web service. If the MCP specification is implemented faithfully, an MCP client establishes a long-lived HTTP connection with the server, with session management handled by token- based authentication.

The March 26, 2025 release of the Model Context Protocol specification stipulated that where authorization is required, OAuth 2.1 is the appropriate method:

MCP auth implementations MUST implement OAuth 2.1 with appropriate security measures for both confidential and public clients.

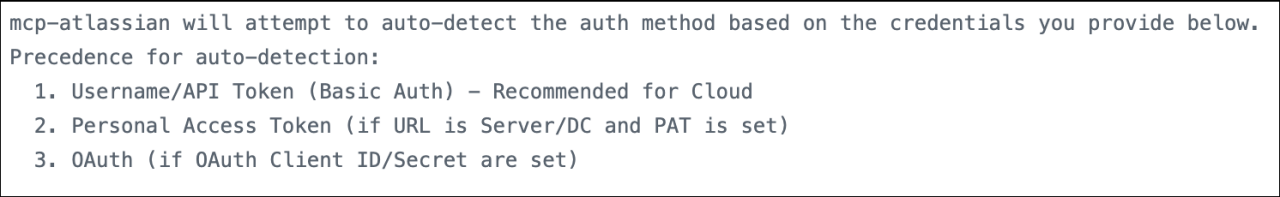

Atlassian was among the first enterprise software vendors to offer a remote MCP server for customers. This offers a simple, OAuth-capable alternative to a community server that preceded it by several months.

A comparison between the official remote MCP server and the local "community" developed local server is instructive.

When the community server discovers authentication methods available in a local .env (configuration) file, any passwords configured for basic authentication takes precedence over any configured Personal Access Tokens, which in turn take precedence over OAuth credentials.

The authors of this plugin plainly state that they have optimized for developer convenience over security.

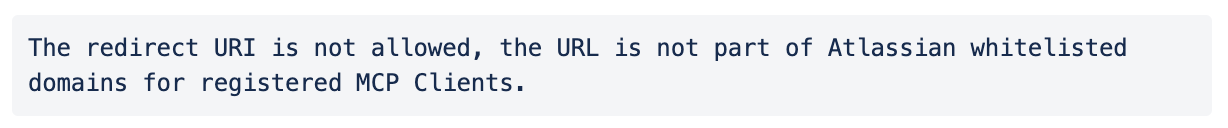

Atlassian's official remote MCP server, by contrast, includes localhost support in order to deliver OAuth-based log-in and consent for all users, including those connecting from local IDEs like Cursor.

This effectively removes the need for developers to copy and paste secrets into local configuration files. The configuration file simply references the remote service, and the user is asked to complete an OAuth Consent after successful authentication.

And unlike Microsoft Copilot, which optimised for choice of authentication methods rather than a specific security outcome, OAuth is the only available authentication method in Atlassian's remote MCP server. Atlassian is also allowlisting which hosts (Al applications) are able to connect to this remote MCP server.

Figure 15: Source: Atlassian

Figure 15: Source: Atlassian

Securing agentic Al

The only question is which OAuth flow to use!

While remote MCP servers based in OAuth provide a more secure and standardized approach than proprietary plugins, the path ahead is far from settled. 20 Some of the remaining security challenges are:

- How can we authorize Al agents to access protected resources, while always keeping the interactive (human) user in the loop?

- How can we reduce the management burden of writing authorization rules for each individual resource at the service provider level?

- How can we provide centralized policies and auditing of authorization grants?

In the remote MCP servers we assessed, Al agents were authorized with the same level of access to services as the user that authorized them. They are acting "on behalf of" a user to the fullest extent of what the user is authorized to do.

This may not meet the bar for CISOs concerned about the risks of connecting Al agents to data they are duty-bound to protect. Enterprise administrators will not be content to let service providers be the final authority on what tools the MCP server provides.

A centralized administrator can't, in the Atlassian example, write policies that allow users to authorize Al agents to read and write Confluence wiki pages, but deny the ability to modify Jira tickets. Administrators can't choose specific projects that they don't want Al agents to access. If the user can access it, so can the agent.

The IETF draft OAuth Identity Assertion Grant, authored by current and former Okta architects, aims to solve this problem. This grant combines two existing standards - the OAuth 2.0 Token Exchange and JWT Profile for OAuth 2.0 Authorization Grants into a grant that provides enterprise control and visibility.

Using this approach, administrators are able to configure centralized policies that ensure an SSO-protected user can authorize an Al agent to access data in multiple applications where a trust relationship has already been established.

The CISO would again be able to limit the scope of what clients (in this case, Al agents) can access in a protected resource. Okta is working with Independent Software Vendors (ISVs) to bring these capabilities to customers under the newly-announced Cross App Access.

Concluding remarks

As an industry we now have some important decisions to make in order to safely enjoy the benefits of connecting protected resources to agentic Al.

We must resist the temptation to repurpose authentication methods that were already unsuited to connecting systems over the public internet, let alone systems that can act with autonomy. As Al agents seek and are granted broader sets of permissions, the "blast radius" of any single compromise will be greatly amplified. A single breach could expose significantly more data and critical systems than before.

We must instead adopt flows that are built for the Al era - narrowly scoped, user-delegated access flows that use ephemeral, auditable tokens, providing the CISO with some long overdue control and visibility.

Appendix: Protective Controls

Recommendations for Service Providers

- Embrace OAuth 2.1 as the minimum viable authorization model for Model Context Protocol (MCP) servers.

- Subscribe to updates on MCP to keep abreast of new developments.

Recommendations for Developers

- Restrict the use of static API tokens to development and test environments only (no production data) and apply the minimum scopes required.

- When developing locally, use OS-level secret vaults (MacOS keychain, Windows Credential Manager) to dynamically fetch secrets at runtime.

- Modify the permissions of .env and other configuration files as well as the local log files of Al applications such that only your user account can read or modify them.

- List all configuration and log files in .gitignore to guard against accidentally committing them to version control systems.

Recommendations for Security Teams

- Restrict development activities to corporate-issued, hardened workstations.

- Require phishing resistant authentication for access to corporate resources.

- Use dedicated secrets management solutions for production credentials.

- Manage and govern membership of groups with access to container resources, and ensure the docker daemon (process) is configured to avoid exposure.

- Require OAuth 2.1 flows to authorize client access to corporate resources.

- For use cases where the risks of using static API tokens are accepted:

- Educate developers about the risks of using with long-lived tokens.

- Allowlist requests using the token to the known IP range of the corresponding MCP server.

- Deny interactive access to applications using the service account linked to the API token, or in the very least require high-assurance multifactor authentication challenges to access it.

- Proactively hunt for tokens stored in plaintext on servers, in files, in code repositories, in logs and in messaging and collaboration apps.

- Monitor for abuse of tokens.