Okta Threat Intelligence has conducted a large-scale analysis revealing that the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) IT worker scheme threatens nearly every industry that hires remote talent.

While public reporting has primarily focused on DPRK nationals targeting software development roles at major US technology companies, our analysis shows that this threat is not limited to the tech sector, nor the US. North Korean IT Workers (ITW) now pose a real threat to a wide range of industries. Impacted industries include finance, healthcare, public administration, and professional services across a growing number of countries. This widespread scheme aims to gain illicit employment and — in some cases — steal sensitive data.

Just how expansive is this threat? Our analysis of thousands of examples from our sample of DPRK ITW activity found that Information and Technology organizations represent only half of the targeted entities. We also found that over a quarter (27%) of targeted entities are based in countries other than the United States.

Okta Threat Intelligence observed examples of DPRK-linked actors progressing through multiple interviews for the same roles. While we are not privy to every organization’s hiring and onboarding processes, evidence of post-onboarding corporate activities was observed in multiple organizations across different verticals, supporting the theory that a broad, “scatter-gun” approach to job application and interviewing has been successful enough to make it a worthwhile endeavour for the DPRK regime to continue and expand.

It’s essential that organizations in all industry sectors and countries are made aware that DPRK-linked actors have applied or are likely to apply for advertised remote technical roles and to implement the crucial extra steps required to make their organization a harder target.

Inside the investigation: 130+ identities and thousands of targeted companies

Using a combination of internal and external data sources, Okta Threat Intelligence tracked over 130 identities operated by facilitators and workers participating in the DPRK ITW scheme. We linked these actors to over 6,500 initial job interviews across more than 5,000 distinct companies up until mid-2025.

In order to avoid tipping off the threat actors as to how we gained visibility of their activities, Okta Threat Intelligence is deliberately withholding some details about our research methodology. Our confidence in the data has been validated by ongoing briefings with industry peers, law enforcement agencies, and targeted organizations.

Notably, there are surface similarities between DPRK IT Workers and non-DPRK “overemployment” workers such as remote work patterns, financial motivations, deception techniques and geographic origins. Okta assesses any given identity as DPRK-aligned based on a combination of technical indicators, behavioural patterns and first-hand employer reporting. Additionally, we anticipate that the 130 identities Okta Threat Intelligence is tracking reflect only a small sample of total active DPRK ITW activity.

An expanding problem

For at least the past five years, the heavily-sanctioned DPRK has mobilized individuals by the thousands into neighbouring countries, tasking them with gaining illicit employment in developed countries. DPRK IT Workers rely on identity fraud and the collaboration of facilitators in targeted countries to help them gain and maintain employment.

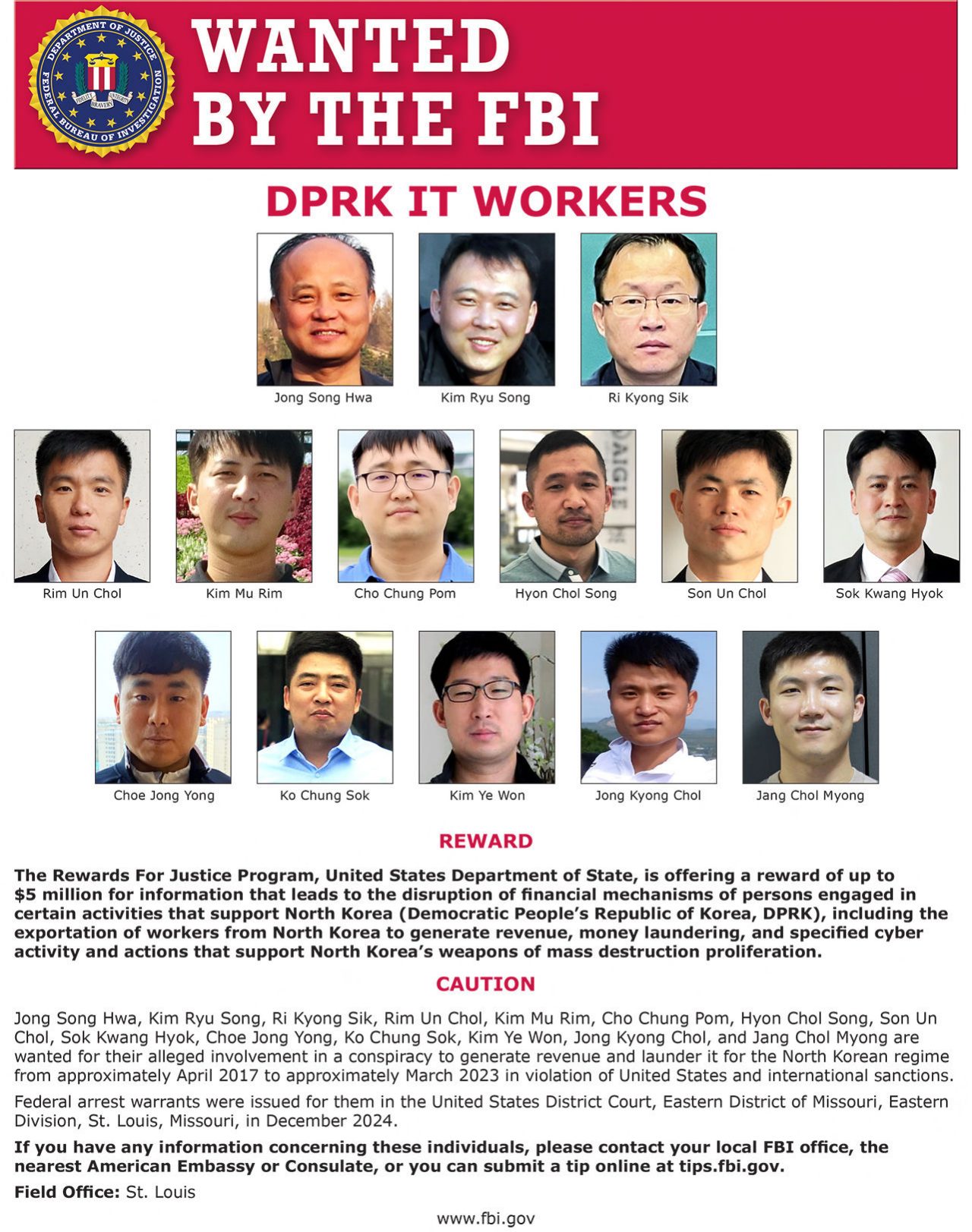

FBI DPRK ITW wanted poster

FBI DPRK ITW wanted poster

Okta’s latest research reveals both the breadth of industries being targeted and the sustained duration of this operation, indicating a far-reaching and evolving effort to infiltrate businesses of all types in developed countries. A relatively small number of people were able to identify job advertisements, generate and submit tailored applications (including CVs, cover letters, and supporting materials), pass initial recruiter or HR screening, and secure remote interviews at scale.

While the primary objective of the ITW scheme remains financial gain through the payment of wages, there are numerous reports surfacing of data theft and extortion attempts against organizations that have unknowingly employed and later moved to terminate these workers.

Occasional data exfiltration and extortion incidents — including ransomware-related activity — highlights the dual-use nature of this campaign. The access afforded by placing DPRK-linked personnel inside Western organizations provides a significant intelligence and disruption capability should the DPRK regime decide to use it. The potential for broader access and technical collection built through this long-running operation should be of concern to governments and organizations across most sectors of the economy.

DPRK ITW units appear to be learning from earlier missteps and are targeting a greater number of industries in a greater number of countries. Targeted entities in those countries now face a mature, experienced threat that has achieved the necessary success to have been granted a level of “creative freedom” over targeted verticals and the tools, techniques, and procedures they use to gain employment.

It's possible that increased awareness of this threat — as well as government and private sector collaborative efforts to identify and disrupt their operations — may be an additional driver for them to increasingly target roles outside of the US and IT industries.

The DPRK is widening its targets from big tech to hospitals, banks, and beyond

Our research demonstrates a clear progression in the industries and roles being targeted in the ITW scheme.

While DPRK ITW overwhelmingly seek remote software engineering positions, DPRK nationals are increasingly observed applying for remote finance positions (payments processors, etc.) and engineering roles. This suggests that remote roles of any description are in scope for the scheme. So long as the application, interview process, and the work itself can be performed remotely, the DPRK will attempt to use the opportunity to collect financial payment.

Our analysis confirms that job applications extend across nearly every major industry vertical. Over the past four years, we can observe a steady increase in the number of sectors where ITW have successfully applied for and attended job interviews. As expected, large technology firms — especially those that develop software — remain the highest-volume targets. However, other verticals — including finance, healthcare, public administration, and professional services — consistently emerge in our data set, demonstrating an ongoing and wide-ranging campaign.

There are a number of plausible explanations for the distribution of interviews across industry verticals:

The distribution is a function of which industries advertise the most remote software engineering roles. Even among industries that advertise the most for software engineers, certain categories of technology sector workers — such as blockchain technologies or artificial intelligence — show a rise in the amount of interviews that appears proportional to increased demand for developers and engineers.

The distribution reflects a deliberate targeting of industries of interest to the DPRK regime for purposes other than revenue generation, and/or the specializations or experience of specific individuals.

We cannot rule out the possibility that these individuals simply have little regard for the actual nature or business of targeted companies beyond the remote nature of the role.

The most targeted positions remain in remote software development roles (e.g., React, full stack, Java), with occasional clerical or specialist outliers such as bookkeeping, payment processing, and engineering support. Our timeline analysis also reveals distinct troughs in interview activity coinciding with US and Western holiday periods, likely reflecting seasonal hiring slowdowns rather than a change in adversary intent.

A deeper look at DPRK-targeted verticals

Okta Threat Intelligence selected a subset of verticals for deeper analysis to illustrate why they are targeted, and the potential impact of successful infiltration. Although examples are drawn from specific industries, the implications apply broadly and serve as a call-to-action for all organizations.

Software development and IT consulting

DPRK IT Workers continue to focus overwhelmingly on remote software development and IT consulting roles. This includes not only direct employment at technology companies, but also placements at large outsourcing and service providers. These positions offer relatively high wages, access to high-value codebases, infrastructure, and development pipelines while also being abundant and often remote.

Okta’s research shows that these actors systematically identify advertised roles, craft credible resumes and cover letters, pass initial HR screening, and secure interviews at scale. The combination of remote work, contract hiring, and distributed teams creates an environment where traditional background checks and identity verification may be weaker, and ongoing or recurrent identity verification non-existent. This exposure is amplified in IT consultancies, where workers are often embedded with multiple client organizations, increasing the risk of lateral access. Okta Threat Intelligence also observed significant use of freelancer marketplace platforms by these actors.

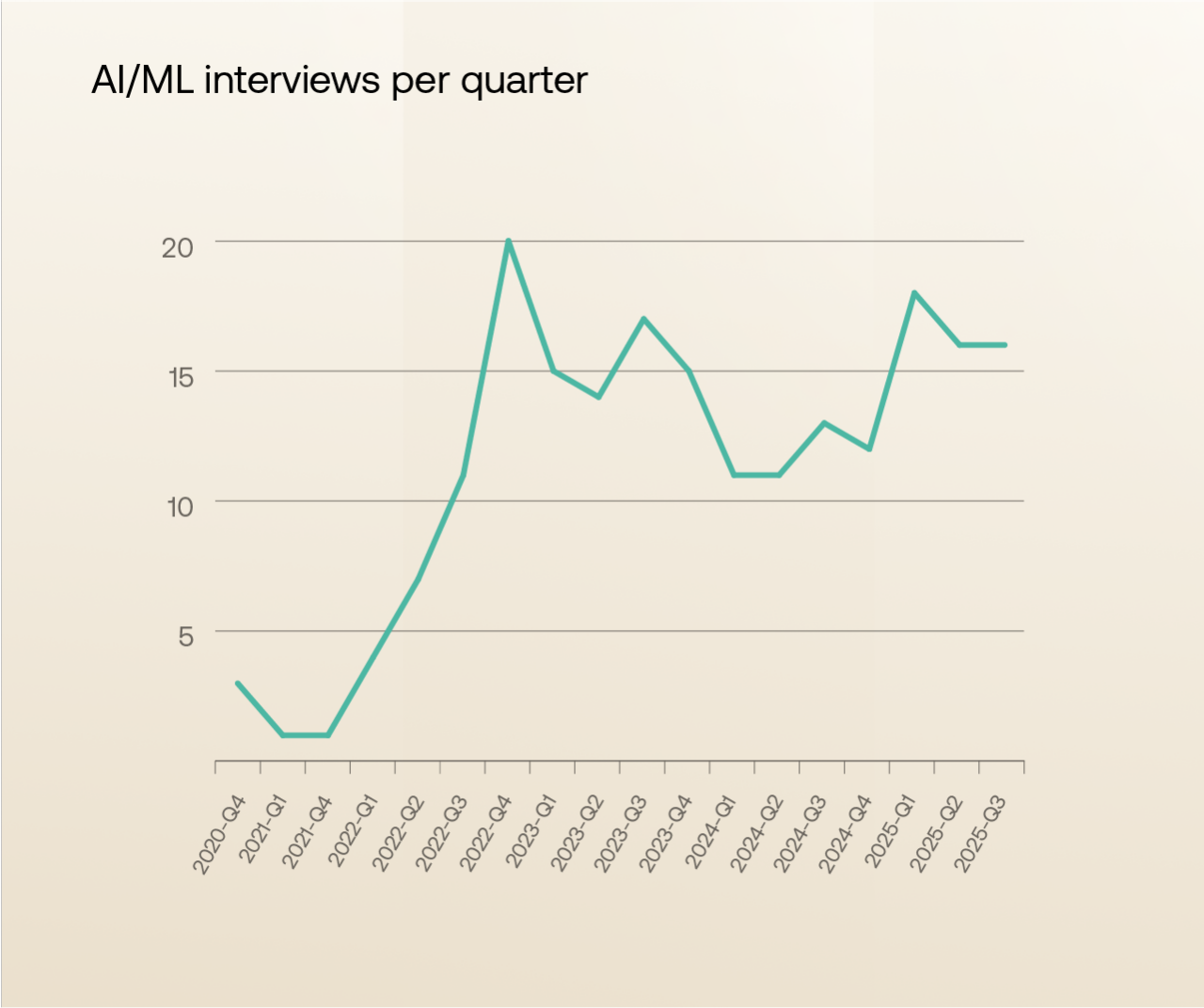

Artificial intelligence

Since mid-2023, Okta has observed a marked increase in DPRK-linked job interviews within AI-focused organizations, including both “pure” AI companies and businesses incorporating AI into existing products and platforms. This surge coincides with the broader expansion of the AI sector and the rush to scale engineering teams — conditions that can reduce the rigour of applicant screening and onboarding.

While some of this rise may simply mirror the overall boom in AI hiring, the exposure of sensitive intellectual property, model-training data, and proprietary algorithms makes this sector especially attractive for state-linked actors. Okta assesses that DPRK IT Workers are likely applying opportunistically to the expanding number of AI positions rather than diverting resources from other sectors. However, the dual-use potential of access to AI systems — particularly for model manipulation or future offensive cyber operations — heightens the strategic risk.

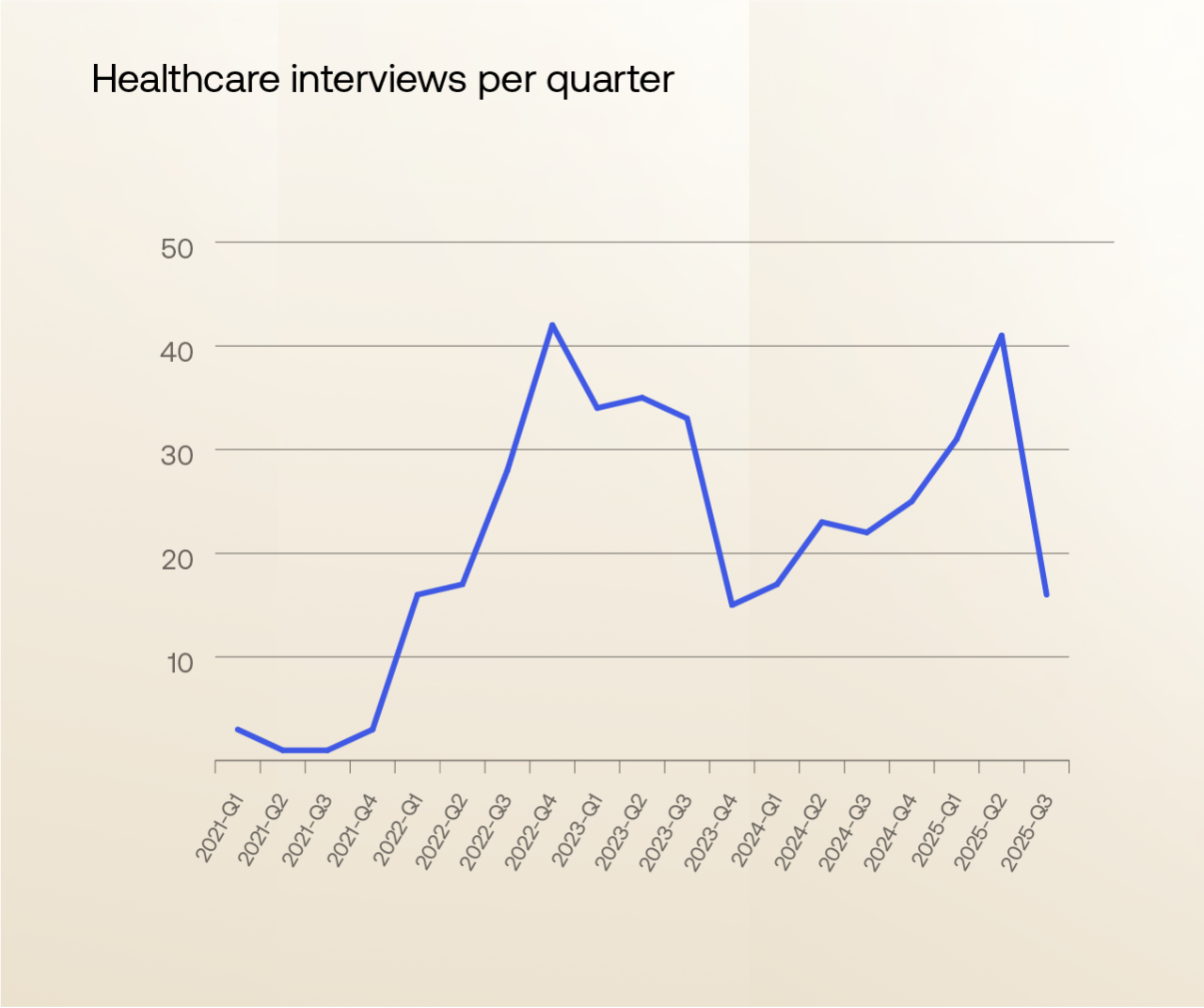

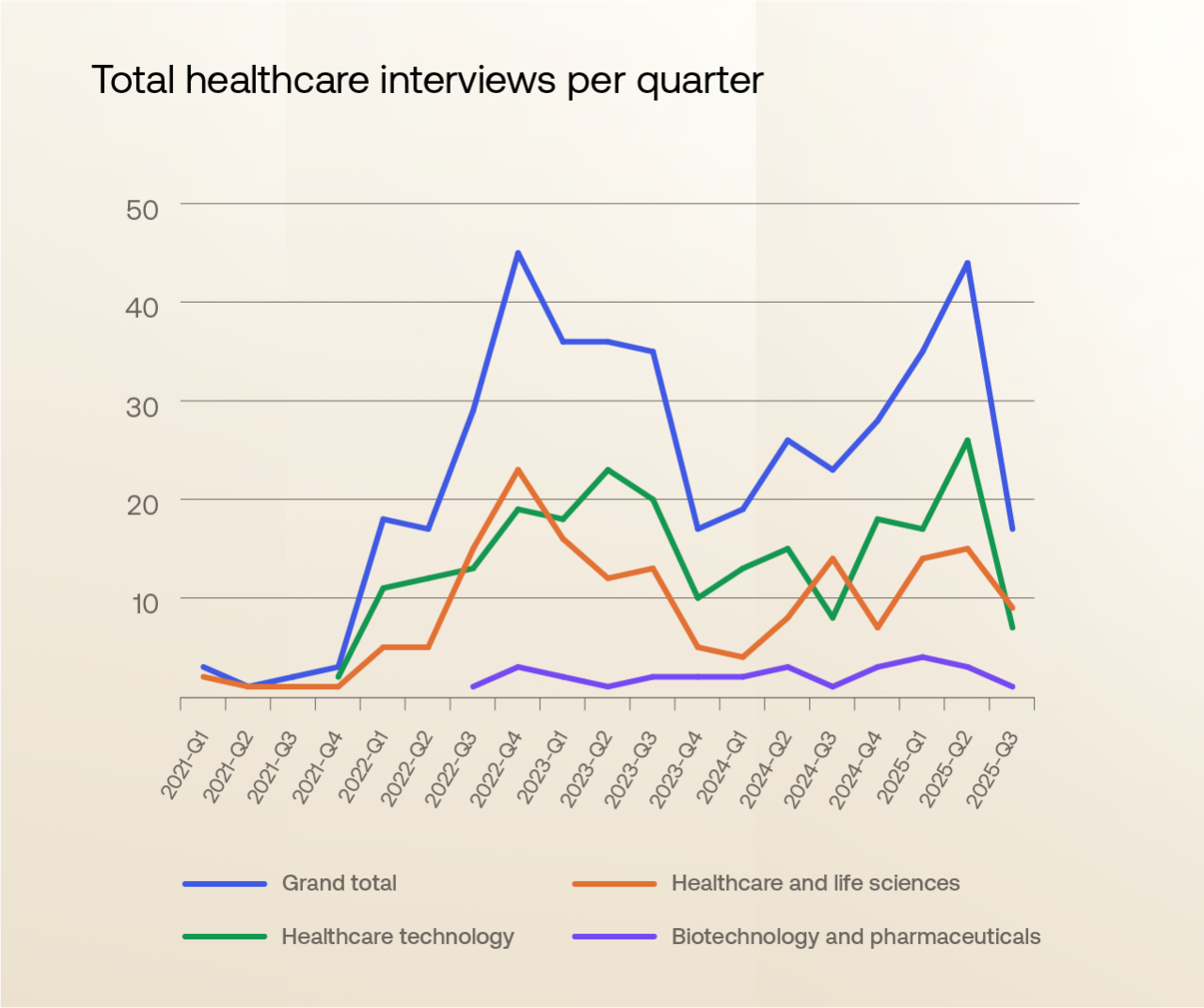

Healthcare and medical technology

More surprisingly, we observed a sustained number of DPRK-linked job interviews among healthcare and medical technology organizations. Most of the targeted roles focus on mobile application development, customer service systems, and electronic record-keeping platforms (directly with healthcare-aligned technology providers, rather than generic service companies). These areas provide potential access to sensitive personally identifiable information (PII), clinical workflows, and health data infrastructure.

The overlap between technology and healthcare has transformed the sector into a high-value target. While medical-focused organizations can often be well-versed in detecting “traditional” false medical credentials or a concerning work history, IT workers and contingent coders may not be afforded the same level of initial or ongoing scrutiny. Healthcare organizations may be under-resourced in insider-threat detection to counter fraudulent employment attempts, relying on traditional recruitment processes that may not catch sophisticated impostors.

In the US, hiring individuals linked to sanctioned countries to handle protected health information could carry significant regulatory implications (e.g., HIPAA violations).

Okta Threat Intelligence assesses that DPRK-linked IT Workers may not yet be systematically targeting healthcare, but are exploiting the abundance of software development roles as the industry digitises — raising the stakes for data security and patient privacy. However, the sensitivity of Healthcare PII would make it particularly vulnerable to data theft and extortion.

Financial services

DPRK IT workers consistently interview for roles in the global financial sector. Targeted entities include traditional banking institutions and insurance firms, as well as modern FinTech companies and cryptocurrency-related organizations.

This offers the DPRK opportunities for direct access to high-value financial infrastructure, including payment processing systems, customer data and other financial data.

The roles targeted have expanded beyond software development to include back-office and financial processing roles in areas like payroll and accounting. This shift indicates an understanding on the part of the DPRK that there are other types of tasks, beyond software engineering, that provide similar opportunities: a targeted entity must be prepared to hire remotely, and a DPRK knowledge worker must be able to demonstrate some level of competency to perform it.

The reliance of financial services on third-party recruiters and contractors for specialized talent creates an environment where identity verification is not performed directly by the hiring organization. This exposure is particularly acute in the Decentralized Finance (DeFi) and cryptocurrency sub-sectors, where a culture of rapid, remote hiring can create significant gaps in vetting, allowing actors to gain trusted access to digital asset treasuries and core protocols.

Government and public administration

Okta observed a small but persistent stream of job interviews between DPRK-linked IT Workers and US state and federal government departments between 2023 and 2025, with additional examples in Middle Eastern and Australian government entities. Although our data does not confirm whether any of these interviews resulted in employment, the attempts demonstrate that government agencies are not immune to the campaign.

More significant is the exposure to public administration via government contractors, service providers and consultancies. These organizations often have extensive access to government networks and sensitive projects, but face high hiring volumes, fast turnaround times, and large pools of remote workers. If screening or access controls fail, DPRK actors could gain indirect entry into government systems or sensitive data repositories. Okta assesses that governments and their third-party vendors must adopt rigorous initial and ongoing identity verification and access segregation to reduce the risk of infiltration.

Outsourcing and IT service providers

Large outsourcing and IT service providers appear frequently in Okta’s data, reflecting their constant recruitment for remote, contract-based technical roles — exactly the type of positions DPRK-linked IT Workers seek. These organizations typically advertise at scale and process high volumes of applicants, increasing the chance of an adversary slipping through.

While many such firms often maintain robust background checks and security controls, the size of their contingent workforces and the embedded nature of their staff in client environments create systemic risk. Any compromise at a service provider can cascade into multiple customer organizations, amplifying the potential impact. Okta assesses that organizations should treat contractor and service-provider staff as potential insider threats and require of their vendors similar identity verification, monitoring, and access controls as used for direct employees. Business processes and vendor access to data and systems should be strictly limited to the absolute minimum required, strictly audited, and subject to rigorous risk assessment.

The global reach of the threat

Okta Threat Intelligence analysis reveals, as expected, that the vast majority of targeted roles (73%) were advertised by US-based firms. Examples of the DPRK IT Worker campaign were first identified in the US and have continued there at scale. There is likely to also be some inherent biases in the data set we analyzed that skew our sample toward US-based targets.

That being said, our analysis reveals a significant expansion of ITW operations into other countries (27% of the total/non-US), often by the same DPRK actors that have typically targeted roles in the US. UK, Canada, and Germany each account for over 2% of the total observations (each accounting for approximately 150 - 250 roles).

Evolving threat from a mature workforce

Okta assesses that as the focus of the DPRK IT Worker operation spreads globally, the threat to employers in newly targeted countries is elevated. Years of sustained activity against a broad range of US industries have allowed DPRK-aligned facilitators and workers to refine their infiltration methods. Consequently, they are entering new markets with a mature, well-adapted workforce capable of bypassing basic screening controls and exploiting hiring pipelines more effectively. New markets that may view the ITW scheme as a “US big tech problem” are less likely to have invested time and effort in maturing their insider-threat programs. The educational, technical, and managerial aspects of such a program require some time and effort to become effective.

Okta Threat Intelligence’s research shows a large volume of initial job interviews granted to DPRK-linked IT Workers across multiple verticals. At this time, we have less confidence in observations about which applications advanced beyond a first interview. Our sample suggests that at most, 10% of these candidates progressed to follow-up interviews.

This success rate should not be reassuring to employers. Okta only analyzed a small subset of the understood total number of fraudulent identities linked to DPRK IT Worker operations. At the scale of this activity, even a small number of candidates that successfully progress to second or third interviews represent a significant threat. It takes only one compromised hire — particularly in a remote privileged or high-access role — to allow adversaries to steal data, disrupt systems, or damage reputation and trust with customers. Software development roles often require elevated access to sensitive data and systems, and these permissions are often granted from the commencement of employment.

These actors have been observed using diverse online language and technical education services in order to bolster their employable skills. They also utilize AI services in their employment attempts.

Response to “market pressure”?

Threat actors in the ITW scheme have historically demonstrated less technical sophistication than their counterparts in DPRK espionage and ransomware operations. This has not diminished their success. DPRK ITW operators have successfully earned tens of millions of dollars for the regime, and we have observed sufficient variation in their tactics over time to conclude that they now enjoy significant autonomy.

But the ITW operation now faces a new threat - an increasing awareness and coordinated disruption of their activities. Scrutiny of the DPRK ITW scheme within its most targeted vertical, the US tech sector, has likely disrupted its revenue generation.

DPRK units tasked with espionage and ransomware operations would now view the ITW hiring model as a vector not to obtain incidental employment and wages, but rather as an opportunity for targeted, persistent data theft and extortion. There are early indications that ITW access is already being abused for these purposes.

Organizations that hire these individuals currently face risks related to sanctions and reputational damage. In the future, they may face deliberate and targeted data theft and extortion operations that exploit the very same access.

Key implications for targeted organizations

Okta’s findings reveal that the DPRK’s IT Worker operation is not a niche threat confined to large technology companies. It’s a widespread, long-term campaign targeting organizations across almost every vertical. This means any organization offering remote or hybrid roles — especially in software development, IT services, or other knowledge-worker disciplines — is a potential target.

The operation’s scale and sophistication demonstrate that traditional recruitment processes alone are insufficient to prevent infiltration. Each compromised hire can provide the DPRK with:

Direct financial gain (salary payments diverted to the regime)

Privileged internal access to sensitive systems, data, and networks

Operational leverage for ransomware, extortion, or follow-on cyber activity

Loss of commercially-sensitive corporate secrets

Strategic intelligence collection and access to support future offensive operations

Additionally, organizations unwittingly hiring DPRK actors potentially risk de facto breach of sanctions obligations, and associated legal exposure.

Organizations should therefore adopt a layered defense, including rigorous identity verification during recruitment, ongoing monitoring of the access and behaviour patterns of remote workers, and a clear incident-response plan for managing insider or supply-chain threats.

Steps to take to counter this threat

Okta Threat Intelligence assesses that organizations across all verticals — particularly those advertising remote or contract roles — should adopt a layered and proactive approach to recruitment, onboarding, and insider-threat monitoring. Okta recommends:

1. Strengthen applicant identity verification

Require verifiable government-issued ID checks at multiple stages of recruitment and employment

Cross-check stated locations with IP addresses (include VPN usage detection), time-zone behaviour, and payroll banking information.

Use accredited third-party services to authenticate identity documents, prior employment, and academic credentials

2. Tighten recruitment and screening processes

Train HR and recruiters to identify red flags. Encourage processes that would identify whether a candidate is swapped out between rounds of interviews. Teach them to identify behavioural cues such as poor knowledge of the area they claim to reside in, a refusal to meet in person, a refusal to turn on camera or remove background filters during interviews, or interviewing using a very poor internet connection. Identify duplicated résumés, inconsistent timelines, mismatched time zones and unverifiable references. Assess the candidate’s online footprint and social media presence against the information provided. Where evidence of previous work is provided, investigate whether these projects were simply cloned from the repositories of legitimate user profiles.

Verify the history of edits to CVs and PDFs in document metadata and other technical “tells” associated with duplication and reuse.

Add structured technical and behavioural verification (live coding or writing performed under recruiter observation).

Require corporate email references (not free webmail) and confirm via outbound call to the main switchboard numbers of the reference organization.

3. Enforce role-based and segregated access controls

Default new or contingent workers to least-privilege profiles and unlock additional access once probationary checks are complete.

Segment development, testing and production; require peer review and approval workflows for code merges and deployments.

Monitor for anomalous access patterns (large data pulls, off-hours logins from unexpected geos/VPNs, credential sharing).

4. Monitor contractors and third-party service providers

Where possible, contractually mandate ongoing identity verification standards, background checks, strong authentication policies, device-security baselines and rights to audit.

Require named-user accounts (no shared logins or internal service accounts where possible) and separate tenant/project access for each client environment.

5. Implement insider-threat and security awareness programs

Establish a dedicated insider-risk function or at least a working group spanning HR, Legal, Security, and IT.

Provide targeted training for recruiters, hiring managers, and technical leads on ITW tradecraft and screening controls.

Educate and empower hiring managers and staff members to observe and submit reports of potentially strange behaviour by their peers that raise questions as to their identity, goals, and locations.

Create safer reporting channels for suspicious behaviour or candidate concerns.

6. Coordinate with law enforcement and industry peers

Share indicators of compromise and suspicious candidate patterns with national cybercrime units and ISAC/ISAO groups.

Develop methods for the “insider-risk” group to receive and action indicators (email addresses, IP addresses, VPN providers, document creation, and behavioural indicators) and be prepared to “share back” relevant findings.

Actively participate in information-sharing forums to track evolving ITW tactics and tooling.

7. Conduct regular risk assessments and red-team exercises

Model insider and malicious contractor attack paths; quantify potential business impact.

Perform red team exercises that test the hiring pipeline (simulated DPRK application and interviews) to assess identity verification processes.

Update incident response plans to include scenarios involving malicious insiders, compromised contractors, and expedited access revocation.

Conclusion

Okta’s analysis demonstrates that the DPRK IT Worker campaign is a large-scale and sustained operation. While it originally targeted US technology companies, the campaign now spans almost all sectors and multiple geographies.

The scale and duration of activity indicate a systematic effort to obtain financial resources, technical access, and strategic intelligence inside targeted organizations. A relatively small number of DPRK-aligned identities has generated thousands of interviews, evidencing both persistence and process maturity. Despite wide-spread awareness of this threat, the interview attempts, targeting, and methodology continues to grow and evolve.

While payroll diversion remains the most visible motivator, the strategic risk extends far beyond salaries. Successful ITW placement can enable data exfiltration, operational disruption, and the quiet establishment of internal access footholds that may be leveraged for espionage, coercion, or future cyber operations.

Organizations that still view this as a “big tech only” issue risk underestimating their exposure. The evidence presented in this report should serve as a call-to-action to harden recruitment and identity verification controls, elevate monitoring of contractors and third-party providers, and ensure incident-response plans explicitly address insider and supply-chain entry vectors.

With early awareness, rigorous verification, and coordinated defence, organizations can materially reduce the likelihood of hiring fraudulent candidates and limit any potential impact arising from infiltration.